It took me fifteen years to discover that I had no talent for writing, but I couldn't give it up because by that time I was too famous.

Robert Benchley

Monday, 28 February 2011

Quote of the day

Legos

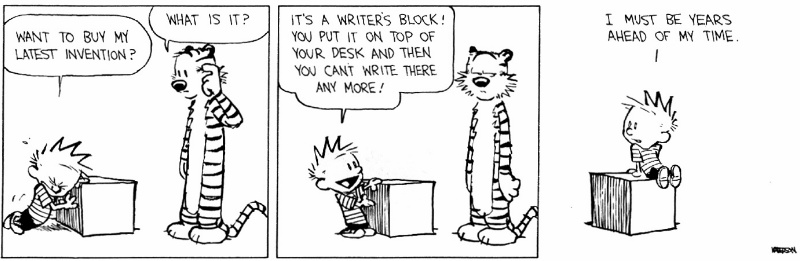

The eternal question: Is it better to read great authors or just leave it at making Legos figures?

Sunday, 27 February 2011

Saturday, 26 February 2011

Friday, 25 February 2011

Quote of the day

The difference between a democracy and a dictatorship is that in a democracy you vote first and take orders later; in a dictatorship you don't have to waste your time voting.

Charles Bukowski

Thursday, 24 February 2011

Quote of the day

Life is intrinsically, well, boring and dangerous at the same time. At any given moment the floor may open up. Of course, it almost never does; that's what makes it so boring.

Edward Gorey

Review: The Unstrung Harp, Or, Mr. Earbass Writes a Novel

The Unstrung Harp, Or, Mr. Earbass Writes a Novel by Edward Gorey (1953).

The Unstrung Harp, Or, Mr. Earbass Writes a Novel by Edward Gorey (1953).Edward Gorey is one of those authors who grows on you–a bit like the moss that accumulates on the shingles of a neglected Victorian Gothic mansion whose owners have fallen on hard times. His macabre cartoons with their laconic captions provide the reader with a tour of a disturbing, gloomy, decadent world where it is always genteel, the 1920s, and perpetually overcast. It's therefore fitting that I'm writing this review on a cold February morning when rolling winter storms keep dumping layers of snow, which then collapse in a few hours into mounds of grey slush. One must be in the proper mood when approaching certain projects.

The Unstrung Harp, Or, Mr. Earbass Writes a Novel is a slim little volume that in words and pictures recounts the efforts of novelist C(lavius) F(rederick) Earbass to come to grips with his latest novel called, for no real reason, The Unstrung Harp. A Creature of habit, Mr Earbass always starts his new novels on the 18th of November of alternative years, but on 17 November discovers that he hasn't the slightest idea for a plot. Clad in his favourite sweater, he tries to get stuck into his work, but he soon finds himself wandering about the house or into town in search of inspiration that keeps eluding him. He's forever waking at night wracked by doubts about the book and it doesn't help that he meets some of his characters wandering about on the landings. Through rewrites, revisions, and up to publication, Mr Earbass is torn between his desires to change every word he's written or just tossing the manuscript in the Thames.

It's a strange tale where jam sandwiches have a bizarre significance, secondhand book stalls pose unfathomable mysteries, and where the creative process is fraught with it's "attendant woes: isolation, writer's block, professional jealousy, and plain boredom". It's also very funny–not in the laugh out loud sense, but in the quietly amused manner. It's a book to read on a silent winter's night with a glass of dry sherry. It's also recommended for any author dealing with the frustrations of writing because it shows that struggling over chapter II or leaving doors open and empty tea cups on the floor is all part of the job.

Though, perhaps, not stuffed fantods under bell jars.

Wednesday, 23 February 2011

Quote of the day

In the 66 years that I have been alive, there has not been one hour, of one day, of one month, of one year, when there has not been a threat aimed at us.

Frederick Forsyth

Tuesday, 22 February 2011

Quote of the day

An archaeologist is the best husband a woman can have. The older she gets the more interested he is in her.

Agatha Christie

Monday, 21 February 2011

Sunday, 20 February 2011

Saturday, 19 February 2011

Friday, 18 February 2011

Quote of the day

I'm sick of following my dreams. I'm just going to ask them where they're going and hook up with them later.

Mitch Hedberg

Thursday, 17 February 2011

Quote of the day

If all the girls who attended the Yale prom were laid end to end, I wouldn't be a bit surprised.

Dorothy Parker

Wednesday, 16 February 2011

Quote of the Day

The Bible tells us to love our neighbors, and also to love our enemies; probably because generally they are the same people.

G. K. Chesterton

Review: Going Postal

Going Postal by Terry Pratchett (2005)

Moist von Lipwig is a conman. He sells dud horses, dud diamonds, dud bonds, and basically anything else that the greedy will snatch up thinking that they're getting the better end of the deal. He's very good at what he does, but one day, the long arm of the law catches up with him. He's sentenced to death, and hanged.

Then his story begins. It turns out that, on the orders of Lord Vetinari, the Patrician of Ankh-Morpork, Lipwig was hanged just enough to die, but not enough to actually kill him. It's a fine distinction that requires an expert hangman. At any rate, Lipwig awakens to discover that Lord Vetinari is offering him the job of Postmaster of Ankh-Morpork. The alternative is walking out a door with a sheer drop of a hundred feet on the other side. After a failed escape attempt and the discovery that his parole officer is an unstoppable golem, Lipwig accepts the position.

Unfortunately, the post office has been effectively closed for years because of an insane backlog of undelivered letters. The building is literally clogged with envelopes and the few remaining postmen are in as bad a shape as the building. Lipwig must therefore effectively reinvent the post office while trying to slip free of the golem. Along the way, Lipwig inadvertently invents the postage stamp; sparks off the hobby of stamp collecting. falls in love with the beautiful, chain-smoking,and violent Adora Belle Dearheart; and makes an enemy of Reacher Gilt, the owner of the Clacks. The Clacks are Ankh-Morpork's mechanical telegraph system that Gilt has been running into the ground because he's had no competition, but now Lipwig is a threat to his monopoly who must be put out of the way. Fortunately, Mr Lipwig has people skills.

None of this would be too bad, except Lipwig discovers that the letters are talking to him.

The 33rd book in Terry Pratchett's Discworld series, Going Postal at first will seem familar to regular readers because the premise is essentially the same as in Pratchett's earlier novel Truth. In that one, we have the same story of one man compressing the entire history of newspaper publishing into a few weeks from the invention of the printing press to the development of the tabloid complete with full colour photo layouts. In many ways, Going Postal feels like a rewrite of the former, though it would be fairer to call it a revisiting. Certainly Lipwig's lovable conman and the golem rights activist Adora Dearheart are much more interesting characters than their earlier versions and Lipwigs flamboyant efforts to promote the post office, complete with sporting a gold suit, are wildly entertaining as we watch him tap dance from one impossible promise to another. Even the post office itself with its superannuated Postmen Pats and their strange initiation rituals are worth the price of admission.

If you decide to read it, order your copy and have it posted to you instead of going to the bookshop or downloading the ebook version. It seems more appropriate.

Moist von Lipwig is a conman. He sells dud horses, dud diamonds, dud bonds, and basically anything else that the greedy will snatch up thinking that they're getting the better end of the deal. He's very good at what he does, but one day, the long arm of the law catches up with him. He's sentenced to death, and hanged.

Then his story begins. It turns out that, on the orders of Lord Vetinari, the Patrician of Ankh-Morpork, Lipwig was hanged just enough to die, but not enough to actually kill him. It's a fine distinction that requires an expert hangman. At any rate, Lipwig awakens to discover that Lord Vetinari is offering him the job of Postmaster of Ankh-Morpork. The alternative is walking out a door with a sheer drop of a hundred feet on the other side. After a failed escape attempt and the discovery that his parole officer is an unstoppable golem, Lipwig accepts the position.

Unfortunately, the post office has been effectively closed for years because of an insane backlog of undelivered letters. The building is literally clogged with envelopes and the few remaining postmen are in as bad a shape as the building. Lipwig must therefore effectively reinvent the post office while trying to slip free of the golem. Along the way, Lipwig inadvertently invents the postage stamp; sparks off the hobby of stamp collecting. falls in love with the beautiful, chain-smoking,and violent Adora Belle Dearheart; and makes an enemy of Reacher Gilt, the owner of the Clacks. The Clacks are Ankh-Morpork's mechanical telegraph system that Gilt has been running into the ground because he's had no competition, but now Lipwig is a threat to his monopoly who must be put out of the way. Fortunately, Mr Lipwig has people skills.

None of this would be too bad, except Lipwig discovers that the letters are talking to him.

The 33rd book in Terry Pratchett's Discworld series, Going Postal at first will seem familar to regular readers because the premise is essentially the same as in Pratchett's earlier novel Truth. In that one, we have the same story of one man compressing the entire history of newspaper publishing into a few weeks from the invention of the printing press to the development of the tabloid complete with full colour photo layouts. In many ways, Going Postal feels like a rewrite of the former, though it would be fairer to call it a revisiting. Certainly Lipwig's lovable conman and the golem rights activist Adora Dearheart are much more interesting characters than their earlier versions and Lipwigs flamboyant efforts to promote the post office, complete with sporting a gold suit, are wildly entertaining as we watch him tap dance from one impossible promise to another. Even the post office itself with its superannuated Postmen Pats and their strange initiation rituals are worth the price of admission.

If you decide to read it, order your copy and have it posted to you instead of going to the bookshop or downloading the ebook version. It seems more appropriate.

Tuesday, 15 February 2011

Quote of the day

A person is a fool to become a writer. His only compensation is absolute freedom.

Roald Dahl

Monday, 14 February 2011

Quote of the day

And the first rude sketch that the world had seen was joy to his mighty heart, till the Devil whispered behind the leaves "It's pretty, but is it Art?"

Rudyard Kipling

When 'Omer Smote 'Is Bloomin' Lyre

When 'Omer smote 'is bloomin' lyre,

He'd 'eard men sing by land an' sea;

An' what he thought 'e might require,

'E went an' took–the same as me!

The market-girls an' fishermen,

The shepherds an' the sailors, too,

They 'eard old songs turn up again,

But kep' it quiet–same as you!

They knew 'e stole; 'e knew they knowed.

They didn't tell, nor make a fuss,

But winked at 'Omer down the road,

An' 'e winked back–the same as us!

Rudyard Kipling

Sunday, 13 February 2011

Saturday, 12 February 2011

Friday, 11 February 2011

Quote of the day

Only in grammar can you be more than perfect.

William Safire

Thursday, 10 February 2011

Quote of the Day

Books aren't written - they're rewritten. Including your own. It is one of the hardest things to accept, especially after the seventh rewrite hasn't quite done it.

Michael Crichton quote

Wednesday, 9 February 2011

Quote of the day

Every branch of human knowledge, if traced up to its source and final principles, vanishes into mystery.

Arthur Machen

Tuesday, 8 February 2011

Quote of the day

The greatest happiness is to scatter your enemy, to drive him before you, to see his cities reduced to ashes, to see those who love him shrouded in tears, and to gather into your bosom his wives and daughters.

Genghis Khan

Monday, 7 February 2011

Quote of the day

Any nation that thinks more of its ease and comfort than its freedom will soon lose its freedom; and the ironical thing about it is that it will lose its ease and comfort too.

W. Somerset Maugham

Review: Last Call for the Dining Car: The Telegraph Book of Great Railway Journeys

Last Call for the Dining Car: The Telegraph Book of Great Railway Journeys. Edited by Michael Kerr (2009)

Though the average London commuter sees rail travel as a necessary evil, railways still have the power to instill powerful feelings of romance in us. Perhaps its because it was the railways that first shrank the world so dramatically that journeys that once took weeks could now be completed in a matter of hours. Perhaps it was the way that rail travel broadened people's horizon's beyond that of their native villages. For whatever reason, even today rail travel revives images of gentility, comfort, adventure, and romance. It makes us think of dining cars and sleepers. Of compartments paneled in wood and backs to the engine. Of steam and porters and attentive stewards. It's the mode of travel of Hercule Poirot and James Bond. Of aristocrats in evening dress and tweedy gentlemen on their way to trout fishing in Scotland. It's traveling not just across geography, but across time to what we like to imagine was a more elegant era.

Last Call for the Dining Car: The Telegraph Book of Great Railway Journeys both feeds and tempers this nostalgia with a collection of articles from the Daily Telegraph and Sunday Telegraph revolving around rail travel over the past 150 plus years. Far from being a dry compendium of newspaper clippings, editor Michael Kerr makes his selection with an eye toward lively writing and entertaining subjects. Separated into general topic sections, the reader can expect to find such gems as John Simpson on Kim Jong Il's armoured train, Lee Langley on the Orient Express in the 1970s, a trip from New Orleans to LA post Katrina, the American rediscovery of Amtrak right after 9/11, the adventure of the world's longest continuous rail journey from London to Hong Kong, train spotter par excellence Michael Palin's musings on meeting InterCity, and the rise and fall (or is it just fall?) of British railway food.

This is not a book to read cover to cover. It's a book to keep on your nightstand and dip into at random before going to sleep. Whether it's the decline of the Orient Express in the 1970s, the beauty of the Trans-Canadian railway, what it's really like aboard the Queen's private train, Queen Victoria's dining habits while travelling, or merely an anecdote about an epic journey made on a platform ticket, Last Call for the Dining Car is sure to entertain. It evokes a nostalgia for a time not so long ago when all transportation systems didn't aspire to the dismal, antiseptic level of service dispensed by airlines and maybe it shows that travel can be something to be enjoyed rather than endured.

Sunday, 6 February 2011

Saturday, 5 February 2011

Friday, 4 February 2011

Quote of the day

Your story is impossible, ridiculus, fantastic, mad, and obviously the ravings of a disordered mind. And I believe every word of it.

Keith Laumer

Review: The Invaders

The Invaders by Keith Laumer (1967)

Like many television series in the days before VCRs, the appetite of fans of the show for more stories was addressed by the issuing of tie-in novels. In the 1960s, such books based on television series were an uneven lot. Some, such as Jame Blish's Star Trek books were boiled down versions of the television episodes. Others were pastiches that could have been turned into screenplays. Others were hack jobs that bore almost no resemblance to the source material. Keith Laumer's two Invaders novels were a peculiar departure. Instead of taking the usual paths, Laumer reinvented the television format to suit the printed page and introduced, I suspect, story elements that he'd been nursing for one of his own novels.

In the television version, David Vincent is an architect who becomes involved when he accidentally witnesses a spaceship landing. The aliens come from a dying world and are preparing the path for their eventual takeover. In their human form they are almost undetectable except for small giveaways such as a malformed little finger or (in black aliens) the palms being black. Vincent's fight with them is a shadow war of the Invaders trying to remain undetected while Vincent tries to draw them into the public spotlight.

In Laumer's version, Vincent is an engineer who, while acting as a consultant, notices strange components being manufactured at factories across the United States. As he collects the components and tries to fit them together, Vincent discovers that they form a ray gun with enough power to literally set off a volcano. As in the series, the Invaders are infiltrating human society, but not very successfully because they are putty-faced creatures that can barely pass for human. The reason they're so secretive is because they aren't the advance guard, but rather the sole survivors of the Great Race after their planet was destroyed a million years ago. Numbering only a thousand, they must exterminate the human race quickly and with only limited resources if they are to survive. Vincent's war with them isn't the slow intrigue of the television, but rather of Vincent and the Invaders repeatedly swapping the roles of hunter and hunted as Vincent tracks down the aliens before they can find him.

The plots are also much more action oriented and elaborate than on television with Vincent battling aliens who are bioengineered supermen and especially against Vincent's nemisis the alien Dorn, who survives repeated and fiery defeats at Vincent's hands. The novel is broken into three episodes starting with Vincent's discovery of the aliens, to his battle with Dorn in the booby trapped house of a madman, and Vincent's thwarting of the Invader's grand coup. All the while Laumer instills a sense of urgency as we follow an increasingly battered, exhausted, and shabby David Vincent who must defeat his enemy before his own meager resources run out.

Out of print since its original publication in 1967, The Invaders is a neat little gem that doesn't disappoint, but is doomed to die the death of copyright as the remaining copies succumb to the acid in their cheap paperback pages. Let's hope someone has the foresight to make a digital scan before then.

The Invaders: Alien beings from a dying planet. Their destination : The Earth. Their purpose: To make it their world. David Vincent has seen them. For him, it began one lost night on a lonely country road looking for a short-cut that he never found. It began with a closed, deserted diner...and a man too long without sleep to continue his journey. It began with the landing of a craft from another galaxy. Now, David Vincent knows that the Invaders are here; that they have taken human form. Somehow, he must convince a disbelieving world that the nightmare has already begun.The Invaders (1967) was a true rarity in television history; a truly original series that had an influence far beyond its meager 43-episode run. It's story of a man who unwittingly discovers a secret plot by aliens to take over the Earth, yet can't find the evidence to convince anyone else of the danger introduced television audiences to something that was new to the medium: Stark, unrelenting paranoia. David Vincent's one-man war against an inhuman enemy that could be turn out to be anyone, anywhere was a solid break from the more sedate television fare of the day and provided a template for later series such as the X-Files and V.

Like many television series in the days before VCRs, the appetite of fans of the show for more stories was addressed by the issuing of tie-in novels. In the 1960s, such books based on television series were an uneven lot. Some, such as Jame Blish's Star Trek books were boiled down versions of the television episodes. Others were pastiches that could have been turned into screenplays. Others were hack jobs that bore almost no resemblance to the source material. Keith Laumer's two Invaders novels were a peculiar departure. Instead of taking the usual paths, Laumer reinvented the television format to suit the printed page and introduced, I suspect, story elements that he'd been nursing for one of his own novels.

In the television version, David Vincent is an architect who becomes involved when he accidentally witnesses a spaceship landing. The aliens come from a dying world and are preparing the path for their eventual takeover. In their human form they are almost undetectable except for small giveaways such as a malformed little finger or (in black aliens) the palms being black. Vincent's fight with them is a shadow war of the Invaders trying to remain undetected while Vincent tries to draw them into the public spotlight.

In Laumer's version, Vincent is an engineer who, while acting as a consultant, notices strange components being manufactured at factories across the United States. As he collects the components and tries to fit them together, Vincent discovers that they form a ray gun with enough power to literally set off a volcano. As in the series, the Invaders are infiltrating human society, but not very successfully because they are putty-faced creatures that can barely pass for human. The reason they're so secretive is because they aren't the advance guard, but rather the sole survivors of the Great Race after their planet was destroyed a million years ago. Numbering only a thousand, they must exterminate the human race quickly and with only limited resources if they are to survive. Vincent's war with them isn't the slow intrigue of the television, but rather of Vincent and the Invaders repeatedly swapping the roles of hunter and hunted as Vincent tracks down the aliens before they can find him.

The plots are also much more action oriented and elaborate than on television with Vincent battling aliens who are bioengineered supermen and especially against Vincent's nemisis the alien Dorn, who survives repeated and fiery defeats at Vincent's hands. The novel is broken into three episodes starting with Vincent's discovery of the aliens, to his battle with Dorn in the booby trapped house of a madman, and Vincent's thwarting of the Invader's grand coup. All the while Laumer instills a sense of urgency as we follow an increasingly battered, exhausted, and shabby David Vincent who must defeat his enemy before his own meager resources run out.

Out of print since its original publication in 1967, The Invaders is a neat little gem that doesn't disappoint, but is doomed to die the death of copyright as the remaining copies succumb to the acid in their cheap paperback pages. Let's hope someone has the foresight to make a digital scan before then.

Thursday, 3 February 2011

Quote of the day

I know you've heard it a thousand times before. But it's true - hard work pays off. If you want to be good, you have to practice, practice, practice. If you don't love something, then don't do it.

Ray Bradbury

Wednesday, 2 February 2011

Quote of the day

It is comparatively easy to become a writer; staying a writer, resisting formulaic work, generating one's own creativity - that's a much tougher matter.

Brian Aldiss

Review: Moonraker

Moonraker by Ian Fleming (1955)

For most people, if you mention Moonraker they will immediately think of the 1979 film adaptation that is widely regarded as the worst of the entire Eon Productions Bond series. This is a pity because first, I think that it was only the second worst of the series (Octopussy was flat-out boring) and second, the original novel is widely thought the best of Fleming's Bond books.

Moonraker tells a very straightforward tale about how Bond becomes involved in the case of Hugo Drax; an industrialist who is paying out of his own pocket for the construction of a nuclear missile called Moonraker that he plans to hand over to the British government. A former British soldier who was badly wounded during the war, Drax went from being a horribly scarred amnesiac to one of the great successes of 1950s Britain. To the public, he is a flamboyant, larger than life character who shows that anyone can succeed if they have a bit of drive. To the government, he's the potential savior of the nation. To 007's boss M, there's something fishy about Drax. Why? Because he cheats at cards.

So begins Bond's adventure that starts with his uncovering Drax's card sharping at a posh London club and ends up at the Moonraker test site where the security chief was apparently murdered over a girl a few days before the first test launch. The fact that the man and the girl were both Special Branch undercover agents and that the murderer shouted "Heil Hitler" before turning his gun on itself shows that there is more going on at the Moonraker project than meets the eye.

Despite its economical plot, Moonraker works because of Fleming's remarkable powers of description that can turn one of Bond's meals into fascinating glimpse into a world that few people could experience in his day and is largely lost in the 21st century. Then there is Fleming's his ability to draw vivid characters. The James Bond of the books is not the near self-parody of the films, but rather a complex character with his own doubts and powerful motives that both propel him forward and blind him to important clues. His relationship is far from the bed-them-and-leave-them encounters that his cinematic counterpart indulges in and there is even a bit of poignancy in the mix. Hugo Drax, on the other hand is a frightening character who is rather like sharing the stage with a time bomb. It's apparent from our first meeting with him that there is something repellent about the man, but he remains intriguing as Fleming piques our curiosity about what makes this creature tick.

The highlight of the book comes in the early part when Bond confronts Drax over a game of bridge. I know nothing about the game and when I first read the book as a teenager I was tempted to skip over the chapter, but I soon discovered Fleming's way of making something as commonplace as a parlour game into something as serious as a duel with pistols. What begins as an attempt by Bond to figure out whether or not Drax is a cheat rapidly evolves under Fleming's hand into a personal battle between two powerful personalities who have staked their manhood and a small fortune on the outcome. It is certainly one of the most remarkable passages ever to grace the thriller genre. Small wonder that it ends with a defeated Drax hissing "I should spend the money quickly, Commander Bond."

High living, beautiful women, a plot involving a nuclear missile and a thoroughly nasty villain; what more could one ask of a Bond novel?

For most people, if you mention Moonraker they will immediately think of the 1979 film adaptation that is widely regarded as the worst of the entire Eon Productions Bond series. This is a pity because first, I think that it was only the second worst of the series (Octopussy was flat-out boring) and second, the original novel is widely thought the best of Fleming's Bond books.

Moonraker tells a very straightforward tale about how Bond becomes involved in the case of Hugo Drax; an industrialist who is paying out of his own pocket for the construction of a nuclear missile called Moonraker that he plans to hand over to the British government. A former British soldier who was badly wounded during the war, Drax went from being a horribly scarred amnesiac to one of the great successes of 1950s Britain. To the public, he is a flamboyant, larger than life character who shows that anyone can succeed if they have a bit of drive. To the government, he's the potential savior of the nation. To 007's boss M, there's something fishy about Drax. Why? Because he cheats at cards.

So begins Bond's adventure that starts with his uncovering Drax's card sharping at a posh London club and ends up at the Moonraker test site where the security chief was apparently murdered over a girl a few days before the first test launch. The fact that the man and the girl were both Special Branch undercover agents and that the murderer shouted "Heil Hitler" before turning his gun on itself shows that there is more going on at the Moonraker project than meets the eye.

Despite its economical plot, Moonraker works because of Fleming's remarkable powers of description that can turn one of Bond's meals into fascinating glimpse into a world that few people could experience in his day and is largely lost in the 21st century. Then there is Fleming's his ability to draw vivid characters. The James Bond of the books is not the near self-parody of the films, but rather a complex character with his own doubts and powerful motives that both propel him forward and blind him to important clues. His relationship is far from the bed-them-and-leave-them encounters that his cinematic counterpart indulges in and there is even a bit of poignancy in the mix. Hugo Drax, on the other hand is a frightening character who is rather like sharing the stage with a time bomb. It's apparent from our first meeting with him that there is something repellent about the man, but he remains intriguing as Fleming piques our curiosity about what makes this creature tick.

The highlight of the book comes in the early part when Bond confronts Drax over a game of bridge. I know nothing about the game and when I first read the book as a teenager I was tempted to skip over the chapter, but I soon discovered Fleming's way of making something as commonplace as a parlour game into something as serious as a duel with pistols. What begins as an attempt by Bond to figure out whether or not Drax is a cheat rapidly evolves under Fleming's hand into a personal battle between two powerful personalities who have staked their manhood and a small fortune on the outcome. It is certainly one of the most remarkable passages ever to grace the thriller genre. Small wonder that it ends with a defeated Drax hissing "I should spend the money quickly, Commander Bond."

High living, beautiful women, a plot involving a nuclear missile and a thoroughly nasty villain; what more could one ask of a Bond novel?

Tuesday, 1 February 2011

Quote of the day

I like work; it fascinates me. I can sit and look at it for hours.

Jerome K. Jerome

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)