I did not write it. God wrote it. I merely did his dictation.

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Friday, 31 December 2010

Quote of the day

Dictation and the machine

Over the years, I've used a lot of different ways of conveying words on paper. I've employed pencils, biros, fountain pens, and even a quill (long story). I've also used manual, portable, electric, and electronic typewriters, tape recorders, digital recorders, word processors, PCs, and Web-based software. And I've set my thoughts down on everything from paper to parchment to notebooks to the Cloud. Each of these had their strengths and their weaknesses and most of them I still use as the situation require. Oddly, the older the technology, the more likely I am to use it regularly. I always carry a notebook and pen as a matter of course while the only reason I'd buy a manual typewriter today is because I think it would look good in the living room next to the retro-styled media centre.

Now I'm adding another tool to the literary workshop. At Christmas, my in-laws bought me the Dragon NaturallySpeaking (sic) software. I can't imagine where they got the idea. I suppose it's because I'm a freelance writer and they figured that I was already well-stocked on thesaurae and dictionaries. I couldn't see much use in it, but I've always been interested in VR technology and I found that being able to order my phone to place calls without taking it out of my pocket was suitably futuristic, so I figured what the heck.

Loading the software was the usual pain. Most applications I now use are either downloads or sit on the Web, so popping in the DVD seemed almost old fashioned. There followed the usual round of closing running applications, deactivating anti-virus programmes, giving permissions, entering serial numbers, registering this, restarting that, sacrificing a goat, drawing arcane runes, etc. that I almost forgot what the deuce I was installing. Finally, I got it up and running. Luckily, my monitor already has a microphone installed, so I didn't have to use the cumbersome headset that came with the disc. I have no idea where they got it from, but looked an fit like something from the '90s and wasn't a patch on the tiny microphone/earpiece that I use for online meetings when feedback is frowned upon.

Now I had to teach it how to recognise my voice. This was easier than it might have been because the designers preloaded various accents, so all I had to do was click "British". Unfortunately, there was no Yorkshire via Oxbridge and a stint in rep theatre, so there was still a ways to go. I then had to read some text. Again, the designers were thinking ahead and offered a choice of reading. I picked a Dave Barry piece that would have been very entertaining if I hadn't had to re-read half the sentences several times over for the computers benefit.

At last, the software was configured, up, and running. I propped the reference card in front of my keyboard, and off I went.

Theoretically, you should be able to use NaturallySpeaking to control most functions on you computer. You can tell it to open programs, search the Internet or your computer, move your mouse around, and check your e-mail. Yes, you can do this, but it's hardly practical. The software misunderstands at least a quarter of the time, moving the mouse takes several steps, and the entire process is maddeningly slow. If I'd sprained both my wrists and couldn't type, I'd definitely find the function useful, but otherwise it's hardly worth it.

The other major function of NaturallySpeaking is that you can use it for dictation. Turn the microphone on, open any word processing programming such as Word, OpenOffice, Google Docs, or even an address field and you can tell the computer to write down whatever you say. At first, I thought this could be brilliant. I can type faster than I can talk (and a lot more coherently), but the idea of getting on a roll and having the ability to just dump what I'm saying on the page was tempting.

First the good news: NatruallySpeaking actually does a decent job of understanding what you say and writing it out. Speak clearly and naturally and it will write as happily as an stenographer. It will even format certain things such as dates, addresses, currency, and hyphenate some familiar phrases. This is good. However, when it screws up, it really screws up and you end up with sentences that you'd better remember because you'll never figure it out from what the computer wrote. Also, the programme doesn't punctuate or capitalise, so you have to dictate like you're talking to a typesetter or composing a telegram–remembering to pause and say the words properly or it will write out "comma" and "full stop". It also allows you to spell out words, but since it has trouble telling eh difference between letters and words the results tend to be interesting.

You can, theoretically, also use the porgramme to move around the document, cut and paste, format, and so on, but this is a very difficult process that is hardly worth the effort. I found it much easier to do these tasks by hand. This is complicated, however, by NaturallySpeaking's worst problem, which is how slow it runs. I tried rattling off some copy and soon found that the computer was a page behind me. This can be annoying while working, but it's infuriating when you think the computer simply didn't hear properly. Move the cursor at this point and you'll suddenly find NaturallySpeaking dropping text where it was never meant to go.

So, a complete wash, right? Actually, no. Having played with NaturallySpeaking for the better part of a week, I discovered that it does have a practical application. Sometimes I find myself having to include text that it's either impractical or impossible to scan into an OCR application (handwritten notes are an obvious example) and I loathe having to prop my notebook against a paperweight and type all my scribbles in. With NaturallySpeaking, I can now just read them into the document in question and edit them. It's hardly makes it the killer app, but it saves me a tedious chore. I also find it comforting that I have a back up in case a window crashes shut on my fingers.

Bottom line: A fun toy, has some small uses for the experienced writer. I do imagine, however, that for all its limitations it may find its market among the hopeless hunt-and-peck keyboard jockeys.

Now I'm adding another tool to the literary workshop. At Christmas, my in-laws bought me the Dragon NaturallySpeaking (sic) software. I can't imagine where they got the idea. I suppose it's because I'm a freelance writer and they figured that I was already well-stocked on thesaurae and dictionaries. I couldn't see much use in it, but I've always been interested in VR technology and I found that being able to order my phone to place calls without taking it out of my pocket was suitably futuristic, so I figured what the heck.

Loading the software was the usual pain. Most applications I now use are either downloads or sit on the Web, so popping in the DVD seemed almost old fashioned. There followed the usual round of closing running applications, deactivating anti-virus programmes, giving permissions, entering serial numbers, registering this, restarting that, sacrificing a goat, drawing arcane runes, etc. that I almost forgot what the deuce I was installing. Finally, I got it up and running. Luckily, my monitor already has a microphone installed, so I didn't have to use the cumbersome headset that came with the disc. I have no idea where they got it from, but looked an fit like something from the '90s and wasn't a patch on the tiny microphone/earpiece that I use for online meetings when feedback is frowned upon.

Now I had to teach it how to recognise my voice. This was easier than it might have been because the designers preloaded various accents, so all I had to do was click "British". Unfortunately, there was no Yorkshire via Oxbridge and a stint in rep theatre, so there was still a ways to go. I then had to read some text. Again, the designers were thinking ahead and offered a choice of reading. I picked a Dave Barry piece that would have been very entertaining if I hadn't had to re-read half the sentences several times over for the computers benefit.

At last, the software was configured, up, and running. I propped the reference card in front of my keyboard, and off I went.

Theoretically, you should be able to use NaturallySpeaking to control most functions on you computer. You can tell it to open programs, search the Internet or your computer, move your mouse around, and check your e-mail. Yes, you can do this, but it's hardly practical. The software misunderstands at least a quarter of the time, moving the mouse takes several steps, and the entire process is maddeningly slow. If I'd sprained both my wrists and couldn't type, I'd definitely find the function useful, but otherwise it's hardly worth it.

The other major function of NaturallySpeaking is that you can use it for dictation. Turn the microphone on, open any word processing programming such as Word, OpenOffice, Google Docs, or even an address field and you can tell the computer to write down whatever you say. At first, I thought this could be brilliant. I can type faster than I can talk (and a lot more coherently), but the idea of getting on a roll and having the ability to just dump what I'm saying on the page was tempting.

First the good news: NatruallySpeaking actually does a decent job of understanding what you say and writing it out. Speak clearly and naturally and it will write as happily as an stenographer. It will even format certain things such as dates, addresses, currency, and hyphenate some familiar phrases. This is good. However, when it screws up, it really screws up and you end up with sentences that you'd better remember because you'll never figure it out from what the computer wrote. Also, the programme doesn't punctuate or capitalise, so you have to dictate like you're talking to a typesetter or composing a telegram–remembering to pause and say the words properly or it will write out "comma" and "full stop". It also allows you to spell out words, but since it has trouble telling eh difference between letters and words the results tend to be interesting.

You can, theoretically, also use the porgramme to move around the document, cut and paste, format, and so on, but this is a very difficult process that is hardly worth the effort. I found it much easier to do these tasks by hand. This is complicated, however, by NaturallySpeaking's worst problem, which is how slow it runs. I tried rattling off some copy and soon found that the computer was a page behind me. This can be annoying while working, but it's infuriating when you think the computer simply didn't hear properly. Move the cursor at this point and you'll suddenly find NaturallySpeaking dropping text where it was never meant to go.

So, a complete wash, right? Actually, no. Having played with NaturallySpeaking for the better part of a week, I discovered that it does have a practical application. Sometimes I find myself having to include text that it's either impractical or impossible to scan into an OCR application (handwritten notes are an obvious example) and I loathe having to prop my notebook against a paperweight and type all my scribbles in. With NaturallySpeaking, I can now just read them into the document in question and edit them. It's hardly makes it the killer app, but it saves me a tedious chore. I also find it comforting that I have a back up in case a window crashes shut on my fingers.

Bottom line: A fun toy, has some small uses for the experienced writer. I do imagine, however, that for all its limitations it may find its market among the hopeless hunt-and-peck keyboard jockeys.

Thursday, 30 December 2010

Quote of the day

Happiness is not achieved by the conscious pursuit of happiness; it is generally the by-product of other activities.

Aldous Huxley

"Politics and the English Language" by George Orwell

"Politics and the English Language"

by George Orwell

Most people who bother with the matter at all would admit that the English language is in a bad way, but it is generally assumed that we cannot by conscious action do anything about it. Our civilization is decadent and our language–so the argument runs–must inevitably share in the general collapse. It follows that any struggle against the abuse of language is a sentimental archaism, like preferring candles to electric light or hansom cabs to aeroplanes. Underneath this lies the half-conscious belief that language is a natural growth and not an instrument which we shape for our own purposes.

Now, it is clear that the decline of a language must ultimately have political and economic causes: it is not due simply to the bad influence of this or that individual writer. But an effect can become a cause, reinforcing the original cause and producing the same effect in an intensified form, and so on indefinitely. A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts. The point is that the process is reversible. Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble. If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration: so that the fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers. I will come back to this presently, and I hope that by that time the meaning of what I have said here will have become clearer. Meanwhile, here are five specimens of the English language as it is now habitually written.

These five passages have not been picked out because they are especially bad–I could have quoted far worse if I had chosen–but because they illustrate various of the mental vices from which we now suffer. They are a little below the average, but are fairly representative examples. I number them so that i can refer back to them when necessary:

Dying metaphors. A newly invented metaphor assists thought by evoking a visual image, while on the other hand a metaphor which is technically "dead" (e.g. iron resolution) has in effect reverted to being an ordinary word and can generally be used without loss of vividness. But in between these two classes there is a huge dump of worn-out metaphors which have lost all evocative power and are merely used because they save people the trouble of inventing phrases for themselves. Examples are: Ring the changes on, take up the cudgel for, toe the line, ride roughshod over, stand shoulder to shoulder with, play into the hands of, no axe to grind, grist to the mill, fishing in troubled waters, on the order of the day, Achilles' heel, swan song, hotbed. Many of these are used without knowledge of their meaning (what is a "rift," for instance?), and incompatible metaphors are frequently mixed, a sure sign that the writer is not interested in what he is saying. Some metaphors now current have been twisted out of their original meaning withouth those who use them even being aware of the fact. For example, toe the line is sometimes written as tow the line. Another example is the hammer and the anvil, now always used with the implication that the anvil gets the worst of it. In real life it is always the anvil that breaks the hammer, never the other way about: a writer who stopped to think what he was saying would avoid perverting the original phrase.

Operators or verbal false limbs. These save the trouble of picking out appropriate verbs and nouns, and at the same time pad each sentence with extra syllables which give it an appearance of symmetry. Characteristic phrases are render inoperative, militate against, make contact with, be subjected to, give rise to, give grounds for, have the effect of, play a leading part (role) in, make itself felt, take effect, exhibit a tendency to, serve the purpose of, etc., etc. The keynote is the elimination of simple verbs. Instead of being a single word, such as break, stop, spoil, mend, kill, a verb becomes a phrase, made up of a noun or adjective tacked on to some general-purpose verb such as prove, serve, form, play, render. In addition, the passive voice is wherever possible used in preference to the active, and noun constructions are used instead of gerunds (by examination of instead of by examining). The range of verbs is further cut down by means of the -ize and de- formations, and the banal statements are given an appearance of profundity by means of the not un- formation. Simple conjunctions and prepositions are replaced by such phrases as with respect to, having regard to, the fact that, by dint of, in view of, in the interests of, on the hypothesis that; and the ends of sentences are saved by anticlimax by such resounding commonplaces as greatly to be desired, cannot be left out of account, a development to be expected in the near future, deserving of serious consideration, brought to a satisfactory conclusion, and so on and so forth.

Pretentious diction. Words like phenomenon, element, individual (as noun), objective, categorical, effective, virtual, basic, primary, promote, constitute, exhibit, exploit, utilize, eliminate, liquidate, are used to dress up a simple statement and give an air of scientific impartiality to biased judgements. Adjectives like epoch-making, epic, historic, unforgettable, triumphant, age-old, inevitable, inexorable, veritable, are used to dignify the sordid process of international politics, while writing that aims at glorifying war usually takes on an archaic color, its characteristic words being: realm, throne, chariot, mailed fist, trident, sword, shield, buckler, banner, jackboot, clarion. Foreign words and expressions such as cul de sac, ancien regime, deus ex machina, mutatis mutandis, status quo, gleichschaltung, weltanschauung, are used to give an air of culture and elegance. Except for the useful abbreviations i.e., e.g., and etc., there is no real need for any of the hundreds of foreign phrases now current in the English language. Bad writers, and especially scientific, political, and sociological writers, are nearly always haunted by the notion that Latin or Greek words are grander than Saxon ones, and unnecessary words like expedite, ameliorate, predict, extraneous, deracinated, clandestine, subaqueous, and hundreds of others constantly gain ground from their Anglo-Saxon numbers.* The jargon peculiar to Marxist writing (hyena, hangman, cannibal, petty bourgeois, these gentry, lackey, flunkey, mad dog, White Guard, etc.) consists largely of words translated from Russian, German, or French; but the normal way of coining a new word is to use Latin or Greek root with the appropriate affix and, where necessary, the size formation. It is often easier to make up words of this kind (deregionalize, impermissible, extramarital, non-fragmentary and so forth) than to think up the English words that will cover one's meaning. The result, in general, is an increase in slovenliness and vagueness.

Meaningless words. In certain kinds of writing, particularly in art criticism and literary criticism, it is normal to come across long passages which are almost completely lacking in meaning.† Words like romantic, plastic, values, human, dead, sentimental, natural, vitality, as used in art criticism, are strictly meaningless, in the sense that they not only do not point to any discoverable object, but are hardly ever expected to do so by the reader. When one critic writes, "The outstanding feature of Mr. X's work is its living quality," while another writes, "The immediately striking thing about Mr. X's work is its peculiar deadness," the reader accepts this as a simple difference opinion. If words like black and white were involved, instead of the jargon words dead and living, he would see at once that language was being used in an improper way. Many political words are similarly abused. The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies "something not desirable." The words democracy, socialism, freedom, patriotic, realistic, justice have each of them several different meanings which cannot be reconciled with one another. In the case of a word like democracy, not only is there no agreed definition, but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides. It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic we are praising it: consequently the defenders of every kind of regime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using that word if it were tied down to any one meaning. Words of this kind are often used in a consciously dishonest way. That is, the person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to think he means something quite different. Statements like Marshal Pétain was a true patriot, The Soviet press is the freest in the world, The Catholic Church is opposed to persecution, are almost always made with intent to deceive. Other words used in variable meanings, in most cases more or less dishonestly, are: class, totalitarian, science, progressive, reactionary, bourgeois, equality.

Now that I have made this catalogue of swindles and perversions, let me give another example of the kind of writing that they lead to. This time it must of its nature be an imaginary one. I am going to translate a passage of good English into modern English of the worst sort. Here is a well-known verse from Ecclesiastes:

As I have tried to show, modern writing at its worst does not consist in picking out words for the sake of their meaning and inventing images in order to make the meaning clearer. It consists in gumming together long strips of words which have already been set in order by someone else, and making the results presentable by sheer humbug. The attraction of this way of writing is that it is easy. It is easier–even quicker, once you have the habit–to say In my opinion it is not an unjustifiable assumption that than to say I think. If you use ready-made phrases, you not only don't have to hunt about for the words; you also don't have to bother with the rhythms of your sentences since these phrases are generally so arranged as to be more or less euphonious. When you are composing in a hurry–when you are dictating to a stenographer, for instance, or making a public speech–it is natural to fall into a pretentious, Latinized style. Tags like a consideration which we should do well to bear in mind or a conclusion to which all of us would readily assent will save many a sentence from coming down with a bump. By using stale metaphors, similes, and idioms, you save much mental effort, at the cost of leaving your meaning vague, not only for your reader but for yourself. This is the significance of mixed metaphors. The sole aim of a metaphor is to call up a visual image. When these images clash–as in The Fascist octopus has sung its swan song, the jackboot is thrown into the melting pot–it can be taken as certain that the writer is not seeing a mental image of the objects he is naming; in other words he is not really thinking. Look again at the examples I gave at the beginning of this essay. Professor Laski (1) uses five negatives in fifty three words. One of these is superfluous, making nonsense of the whole passage, and in addition there is the slip–alien for akin–making further nonsense, and several avoidable pieces of clumsiness which increase the general vagueness. Professor Hogben (2) plays ducks and drakes with a battery which is able to write prescriptions, and, while disapproving of the everyday phrase put up with, is unwilling to look egregious up in the dictionary and see what it means; (3), if one takes an uncharitable attitude towards it, is simply meaningless: probably one could work out its intended meaning by reading the whole of the article in which it occurs. In (4), the writer knows more or less what he wants to say, but an accumulation of stale phrases chokes him like tea leaves blocking a sink. In (5), words and meaning have almost parted company. People who write in this manner usually have a general emotional meaning–they dislike one thing and want to express solidarity with another–but they are not interested in the detail of what they are saying. A scrupulous writer, in every sentence that he writes, will ask himself at least four questions, thus: 1. What am I trying to say? 2. What words will express it? 3. What image or idiom will make it clearer? 4. Is this image fresh enough to have an effect? And he will probably ask himself two more: 1. Could I put it more shortly? 2. Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly? But you are not obliged to go to all this trouble. You can shirk it by simply throwing your mind open and letting the ready-made phrases come crowding in. They will construct your sentences for you–even think your thoughts for you, to a certain extent–and at need they will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even from yourself. It is at this point that the special connection between politics and the debasement of language becomes clear.

In our time it is broadly true that political writing is bad writing. Where it is not true, it will generally be found that the writer is some kind of rebel, expressing his private opinions and not a "party line." Orthodoxy, of whatever color, seems to demand a lifeless, imitative style. The political dialects to be found in pamphlets, leading articles, manifestoes, White papers and the speeches of undersecretaries do, of course, vary from party to party, but they are all alike in that one almost never finds in them a fresh, vivid, homemade turn of speech. When one watches some tired hack on the platform mechanically repeating the familiar phrases– bestial atrocities, iron heel, bloodstained tyranny, free peoples of the world, stand shoulder to shoulder –one often has a curious feeling that one is not watching a live human being but some kind of dummy: a feeling which suddenly becomes stronger at moments when the light catches the speaker's spectacles and turns them into blank discs which seem to have no eyes behind them. And this is not altogether fanciful. A speaker who uses that kind of phraseology has gone some distance toward turning himself into a machine. The appropriate noises are coming out of his larynx, but his brain is not involved as it would be if he were choosing his words for himself. If the speech he is making is one that he is accustomed to make over and over again, he may be almost unconscious of what he is saying, as one is when one utters the responses in church. And this reduced state of consciousness, if not indispensable, is at any rate favorable to political conformity.

In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible. Things like the continuance of British rule in India, the Russian purges and deportations, the dropping of the atom bombs on Japan, can indeed be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of the political parties. Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism., question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness. Defenseless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification. Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers. People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps: this is called elimination of unreliable elements. Such phraseology is needed if one wants to name things without calling up mental pictures of them. Consider for instance some comfortable English professor defending Russian totalitarianism. He cannot say outright, "I believe in killing off your opponents when you can get good results by doing so." Probably, therefore, he will say something like this:

The inflated style itself is a kind of euphemism. A mass of Latin words falls upon the facts like soft snow, blurring the outline and covering up all the details. The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one's real and one's declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish spurting out ink. In our age there is no such thing as "keeping out of politics." All issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred, and schizophrenia. When the general atmosphere is bad, language must suffer. I should expect to find–this is a guess which I have not sufficient knowledge to verify–that the German, Russian and Italian languages have all deteriorated in the last ten or fifteen years, as a result of dictatorship.

But if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought. A bad usage can spread by tradition and imitation even among people who should and do know better. The debased language that I have been discussing is in some ways very convenient. Phrases like a not unjustifiable assumption, leaves much to be desired, would serve no good purpose, a consideration which we should do well to bear in mind, are a continuous temptation, a packet of aspirins always at one's elbow. Look back through this essay, and for certain you will find that I have again and again committed the very faults I am protesting against. By this morning's post I have received a pamphlet dealing with conditions in Germany. The author tells me that he "felt impelled" to write it. I open it at random, and here is almost the first sentence I see: "[The Allies] have an opportunity not only of achieving a radical transformation of Germany's social and political structure in such a way as to avoid a nationalistic reaction in Germany itself, but at the same time of laying the foundations of a co-operative and unified Europe." You see, he "feels impelled" to write–feels, presumably, that he has something new to say–and yet his words, like cavalry horses answering the bugle, group themselves automatically into the familiar dreary pattern. This invasion of one's mind by ready-made phrases (lay the foundations, achieve a radical transformation) can only be prevented if one is constantly on guard against them, and every such phrase anaesthetizes a portion of one's brain.

I said earlier that the decadence of our language is probably curable. Those who deny this would argue, if they produced an argument at all, that language merely reflects existing social conditions, and that we cannot influence its development by any direct tinkering with words and constructions. So far as the general tone or spirit of a language goes, this may be true, but it is not true in detail. Silly words and expressions have often disappeared, not through any evolutionary process but owing to the conscious action of a minority. Two recent examples were explore every avenue and leave no stone unturned, which were killed by the jeers of a few journalists. There is a long list of flyblown metaphors which could similarly be got rid of if enough people would interest themselves in the job; and it should also be possible to laugh the not un- formation out of existence**, to reduce the amount of Latin and Greek in the average sentence, to drive out foreign phrases and strayed scientific words, and, in general, to make pretentiousness unfashionable. But all these are minor points. The defense of the English language implies more than this, and perhaps it is best to start by saying what it does not imply.

To begin with it has nothing to do with archaism, with the salvaging of obsolete words and turns of speech, or with the setting up of a "standard English" which must never be departed from. On the contrary, it is especially concerned with the scrapping of every word or idiom which has outworn its usefulness. It has nothing to do with correct grammar and syntax, which are of no importance so long as one makes one's meaning clear, or with the avoidance of Americanisms, or with having what is called a "good prose style." On the other hand, it is not concerned with fake simplicity and the attempt to make written English colloquial. Nor does it even imply in every case preferring the Saxon word to the Latin one, though it does imply using the fewest and shortest words that will cover one's meaning. What is above all needed is to let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way around. In prose, the worst thing one can do with words is surrender to them. When you think of a concrete object, you think wordlessly, and then, if you want to describe the thing you have been visualizing you probably hunt about until you find the exact words that seem to fit it. When you think of something abstract you are more inclined to use words from the start, and unless you make a conscious effort to prevent it, the existing dialect will come rushing in and do the job for you, at the expense of blurring or even changing your meaning. Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one's meaning as clear as one can through pictures and sensations. Afterward one can choose–not simply accept– the phrases that will best cover the meaning, and then switch round and decide what impressions one's words are likely to make on another person. This last effort of the mind cuts out all stale or mixed images, all prefabricated phrases, needless repetitions, and humbug and vagueness generally. But one can often be in doubt about the effect of a word or a phrase, and one needs rules that one can rely on when instinct fails. I think the following rules will cover most cases:

I have not here been considering the literary use of language, but merely language as an instrument for expressing and not for concealing or preventing thought. Stuart Chase and others have come near to claiming that all abstract words are meaningless, and have used this as a pretext for advocating a kind of political quietism. Since you don't know what Fascism is, how can you struggle against Fascism? One need not swallow such absurdities as this, but one ought to recognize that the present political chaos is connected with the decay of language, and that one can probably bring about some improvement by starting at the verbal end. If you simplify your English, you are freed from the worst follies of orthodoxy. You cannot speak any of the necessary dialects, and when you make a stupid remark its stupidity will be obvious, even to yourself. Political language–and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists–is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind. One cannot change this all in a moment, but one can at least change one's own habits, and from time to time one can even, if one jeers loudly enough, send some worn-out and useless phrase–some jackboot, Achilles' heel, hotbed, melting pot, acid test, veritable inferno, or other lump of verbal refuse–into the dustbin, where it belongs.

by George Orwell

Most people who bother with the matter at all would admit that the English language is in a bad way, but it is generally assumed that we cannot by conscious action do anything about it. Our civilization is decadent and our language–so the argument runs–must inevitably share in the general collapse. It follows that any struggle against the abuse of language is a sentimental archaism, like preferring candles to electric light or hansom cabs to aeroplanes. Underneath this lies the half-conscious belief that language is a natural growth and not an instrument which we shape for our own purposes.

Now, it is clear that the decline of a language must ultimately have political and economic causes: it is not due simply to the bad influence of this or that individual writer. But an effect can become a cause, reinforcing the original cause and producing the same effect in an intensified form, and so on indefinitely. A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts. The point is that the process is reversible. Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble. If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration: so that the fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers. I will come back to this presently, and I hope that by that time the meaning of what I have said here will have become clearer. Meanwhile, here are five specimens of the English language as it is now habitually written.

These five passages have not been picked out because they are especially bad–I could have quoted far worse if I had chosen–but because they illustrate various of the mental vices from which we now suffer. They are a little below the average, but are fairly representative examples. I number them so that i can refer back to them when necessary:

- 1. I am not, indeed, sure whether it is not true to say that the Milton who once seemed not unlike a seventeenth-century Shelley had not become, out of an experience ever more bitter in each year, more alien [sic] to the founder of that Jesuit sect which nothing could induce him to tolerate.

- Professor Harold Laski (Essay in Freedom of Expression)

- Professor Lancelot Hogben (Interglossa)

- Essay on psychology in Politics (New York)

- Communist pamphlet

- Letter in Tribune

Dying metaphors. A newly invented metaphor assists thought by evoking a visual image, while on the other hand a metaphor which is technically "dead" (e.g. iron resolution) has in effect reverted to being an ordinary word and can generally be used without loss of vividness. But in between these two classes there is a huge dump of worn-out metaphors which have lost all evocative power and are merely used because they save people the trouble of inventing phrases for themselves. Examples are: Ring the changes on, take up the cudgel for, toe the line, ride roughshod over, stand shoulder to shoulder with, play into the hands of, no axe to grind, grist to the mill, fishing in troubled waters, on the order of the day, Achilles' heel, swan song, hotbed. Many of these are used without knowledge of their meaning (what is a "rift," for instance?), and incompatible metaphors are frequently mixed, a sure sign that the writer is not interested in what he is saying. Some metaphors now current have been twisted out of their original meaning withouth those who use them even being aware of the fact. For example, toe the line is sometimes written as tow the line. Another example is the hammer and the anvil, now always used with the implication that the anvil gets the worst of it. In real life it is always the anvil that breaks the hammer, never the other way about: a writer who stopped to think what he was saying would avoid perverting the original phrase.

Operators or verbal false limbs. These save the trouble of picking out appropriate verbs and nouns, and at the same time pad each sentence with extra syllables which give it an appearance of symmetry. Characteristic phrases are render inoperative, militate against, make contact with, be subjected to, give rise to, give grounds for, have the effect of, play a leading part (role) in, make itself felt, take effect, exhibit a tendency to, serve the purpose of, etc., etc. The keynote is the elimination of simple verbs. Instead of being a single word, such as break, stop, spoil, mend, kill, a verb becomes a phrase, made up of a noun or adjective tacked on to some general-purpose verb such as prove, serve, form, play, render. In addition, the passive voice is wherever possible used in preference to the active, and noun constructions are used instead of gerunds (by examination of instead of by examining). The range of verbs is further cut down by means of the -ize and de- formations, and the banal statements are given an appearance of profundity by means of the not un- formation. Simple conjunctions and prepositions are replaced by such phrases as with respect to, having regard to, the fact that, by dint of, in view of, in the interests of, on the hypothesis that; and the ends of sentences are saved by anticlimax by such resounding commonplaces as greatly to be desired, cannot be left out of account, a development to be expected in the near future, deserving of serious consideration, brought to a satisfactory conclusion, and so on and so forth.

Pretentious diction. Words like phenomenon, element, individual (as noun), objective, categorical, effective, virtual, basic, primary, promote, constitute, exhibit, exploit, utilize, eliminate, liquidate, are used to dress up a simple statement and give an air of scientific impartiality to biased judgements. Adjectives like epoch-making, epic, historic, unforgettable, triumphant, age-old, inevitable, inexorable, veritable, are used to dignify the sordid process of international politics, while writing that aims at glorifying war usually takes on an archaic color, its characteristic words being: realm, throne, chariot, mailed fist, trident, sword, shield, buckler, banner, jackboot, clarion. Foreign words and expressions such as cul de sac, ancien regime, deus ex machina, mutatis mutandis, status quo, gleichschaltung, weltanschauung, are used to give an air of culture and elegance. Except for the useful abbreviations i.e., e.g., and etc., there is no real need for any of the hundreds of foreign phrases now current in the English language. Bad writers, and especially scientific, political, and sociological writers, are nearly always haunted by the notion that Latin or Greek words are grander than Saxon ones, and unnecessary words like expedite, ameliorate, predict, extraneous, deracinated, clandestine, subaqueous, and hundreds of others constantly gain ground from their Anglo-Saxon numbers.* The jargon peculiar to Marxist writing (hyena, hangman, cannibal, petty bourgeois, these gentry, lackey, flunkey, mad dog, White Guard, etc.) consists largely of words translated from Russian, German, or French; but the normal way of coining a new word is to use Latin or Greek root with the appropriate affix and, where necessary, the size formation. It is often easier to make up words of this kind (deregionalize, impermissible, extramarital, non-fragmentary and so forth) than to think up the English words that will cover one's meaning. The result, in general, is an increase in slovenliness and vagueness.

Meaningless words. In certain kinds of writing, particularly in art criticism and literary criticism, it is normal to come across long passages which are almost completely lacking in meaning.† Words like romantic, plastic, values, human, dead, sentimental, natural, vitality, as used in art criticism, are strictly meaningless, in the sense that they not only do not point to any discoverable object, but are hardly ever expected to do so by the reader. When one critic writes, "The outstanding feature of Mr. X's work is its living quality," while another writes, "The immediately striking thing about Mr. X's work is its peculiar deadness," the reader accepts this as a simple difference opinion. If words like black and white were involved, instead of the jargon words dead and living, he would see at once that language was being used in an improper way. Many political words are similarly abused. The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies "something not desirable." The words democracy, socialism, freedom, patriotic, realistic, justice have each of them several different meanings which cannot be reconciled with one another. In the case of a word like democracy, not only is there no agreed definition, but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides. It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic we are praising it: consequently the defenders of every kind of regime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using that word if it were tied down to any one meaning. Words of this kind are often used in a consciously dishonest way. That is, the person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to think he means something quite different. Statements like Marshal Pétain was a true patriot, The Soviet press is the freest in the world, The Catholic Church is opposed to persecution, are almost always made with intent to deceive. Other words used in variable meanings, in most cases more or less dishonestly, are: class, totalitarian, science, progressive, reactionary, bourgeois, equality.

Now that I have made this catalogue of swindles and perversions, let me give another example of the kind of writing that they lead to. This time it must of its nature be an imaginary one. I am going to translate a passage of good English into modern English of the worst sort. Here is a well-known verse from Ecclesiastes:

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.Here it is in modern English:

Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compel the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.This is a parody, but not a very gross one. Exhibit (3) above, for instance, contains several patches of the same kind of English. It will be seen that I have not made a full translation. The beginning and ending of the sentence follow the original meaning fairly closely, but in the middle the concrete illustrations–race, battle, bread–dissolve into the vague phrases "success or failure in competitive activities." This had to be so, because no modern writer of the kind I am discussing–no one capable of using phrases like "objective considerations of contemporary phenomena"–would ever tabulate his thoughts in that precise and detailed way. The whole tendency of modern prose is away from concreteness. Now analyze these two sentences a little more closely. The first contains forty-nine words but only sixty syllables, and all its words are those of everyday life. The second contains thirty-eight words of ninety syllables: eighteen of those words are from Latin roots, and one from Greek. The first sentence contains six vivid images, and only one phrase ("time and chance") that could be called vague. The second contains not a single fresh, arresting phrase, and in spite of its ninety syllables it gives only a shortened version of the meaning contained in the first. Yet without a doubt it is the second kind of sentence that is gaining ground in modern English. I do not want to exaggerate. This kind of writing is not yet universal, and outcrops of simplicity will occur here and there in the worst-written page. Still, if you or I were told to write a few lines on the uncertainty of human fortunes, we should probably come much nearer to my imaginary sentence than to the one from Ecclesiastes.

As I have tried to show, modern writing at its worst does not consist in picking out words for the sake of their meaning and inventing images in order to make the meaning clearer. It consists in gumming together long strips of words which have already been set in order by someone else, and making the results presentable by sheer humbug. The attraction of this way of writing is that it is easy. It is easier–even quicker, once you have the habit–to say In my opinion it is not an unjustifiable assumption that than to say I think. If you use ready-made phrases, you not only don't have to hunt about for the words; you also don't have to bother with the rhythms of your sentences since these phrases are generally so arranged as to be more or less euphonious. When you are composing in a hurry–when you are dictating to a stenographer, for instance, or making a public speech–it is natural to fall into a pretentious, Latinized style. Tags like a consideration which we should do well to bear in mind or a conclusion to which all of us would readily assent will save many a sentence from coming down with a bump. By using stale metaphors, similes, and idioms, you save much mental effort, at the cost of leaving your meaning vague, not only for your reader but for yourself. This is the significance of mixed metaphors. The sole aim of a metaphor is to call up a visual image. When these images clash–as in The Fascist octopus has sung its swan song, the jackboot is thrown into the melting pot–it can be taken as certain that the writer is not seeing a mental image of the objects he is naming; in other words he is not really thinking. Look again at the examples I gave at the beginning of this essay. Professor Laski (1) uses five negatives in fifty three words. One of these is superfluous, making nonsense of the whole passage, and in addition there is the slip–alien for akin–making further nonsense, and several avoidable pieces of clumsiness which increase the general vagueness. Professor Hogben (2) plays ducks and drakes with a battery which is able to write prescriptions, and, while disapproving of the everyday phrase put up with, is unwilling to look egregious up in the dictionary and see what it means; (3), if one takes an uncharitable attitude towards it, is simply meaningless: probably one could work out its intended meaning by reading the whole of the article in which it occurs. In (4), the writer knows more or less what he wants to say, but an accumulation of stale phrases chokes him like tea leaves blocking a sink. In (5), words and meaning have almost parted company. People who write in this manner usually have a general emotional meaning–they dislike one thing and want to express solidarity with another–but they are not interested in the detail of what they are saying. A scrupulous writer, in every sentence that he writes, will ask himself at least four questions, thus: 1. What am I trying to say? 2. What words will express it? 3. What image or idiom will make it clearer? 4. Is this image fresh enough to have an effect? And he will probably ask himself two more: 1. Could I put it more shortly? 2. Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly? But you are not obliged to go to all this trouble. You can shirk it by simply throwing your mind open and letting the ready-made phrases come crowding in. They will construct your sentences for you–even think your thoughts for you, to a certain extent–and at need they will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even from yourself. It is at this point that the special connection between politics and the debasement of language becomes clear.

In our time it is broadly true that political writing is bad writing. Where it is not true, it will generally be found that the writer is some kind of rebel, expressing his private opinions and not a "party line." Orthodoxy, of whatever color, seems to demand a lifeless, imitative style. The political dialects to be found in pamphlets, leading articles, manifestoes, White papers and the speeches of undersecretaries do, of course, vary from party to party, but they are all alike in that one almost never finds in them a fresh, vivid, homemade turn of speech. When one watches some tired hack on the platform mechanically repeating the familiar phrases– bestial atrocities, iron heel, bloodstained tyranny, free peoples of the world, stand shoulder to shoulder –one often has a curious feeling that one is not watching a live human being but some kind of dummy: a feeling which suddenly becomes stronger at moments when the light catches the speaker's spectacles and turns them into blank discs which seem to have no eyes behind them. And this is not altogether fanciful. A speaker who uses that kind of phraseology has gone some distance toward turning himself into a machine. The appropriate noises are coming out of his larynx, but his brain is not involved as it would be if he were choosing his words for himself. If the speech he is making is one that he is accustomed to make over and over again, he may be almost unconscious of what he is saying, as one is when one utters the responses in church. And this reduced state of consciousness, if not indispensable, is at any rate favorable to political conformity.

In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible. Things like the continuance of British rule in India, the Russian purges and deportations, the dropping of the atom bombs on Japan, can indeed be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of the political parties. Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism., question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness. Defenseless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification. Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers. People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps: this is called elimination of unreliable elements. Such phraseology is needed if one wants to name things without calling up mental pictures of them. Consider for instance some comfortable English professor defending Russian totalitarianism. He cannot say outright, "I believe in killing off your opponents when you can get good results by doing so." Probably, therefore, he will say something like this:

"While freely conceding that the Soviet regime exhibits certain features which the humanitarian may be inclined to deplore, we must, I think, agree that a certain curtailment of the right to political opposition is an unavoidable concomitant of transitional periods, and that the rigors which the Russian people have been called upon to undergo have been amply justified in the sphere of concrete achievement."

The inflated style itself is a kind of euphemism. A mass of Latin words falls upon the facts like soft snow, blurring the outline and covering up all the details. The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one's real and one's declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish spurting out ink. In our age there is no such thing as "keeping out of politics." All issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred, and schizophrenia. When the general atmosphere is bad, language must suffer. I should expect to find–this is a guess which I have not sufficient knowledge to verify–that the German, Russian and Italian languages have all deteriorated in the last ten or fifteen years, as a result of dictatorship.

But if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought. A bad usage can spread by tradition and imitation even among people who should and do know better. The debased language that I have been discussing is in some ways very convenient. Phrases like a not unjustifiable assumption, leaves much to be desired, would serve no good purpose, a consideration which we should do well to bear in mind, are a continuous temptation, a packet of aspirins always at one's elbow. Look back through this essay, and for certain you will find that I have again and again committed the very faults I am protesting against. By this morning's post I have received a pamphlet dealing with conditions in Germany. The author tells me that he "felt impelled" to write it. I open it at random, and here is almost the first sentence I see: "[The Allies] have an opportunity not only of achieving a radical transformation of Germany's social and political structure in such a way as to avoid a nationalistic reaction in Germany itself, but at the same time of laying the foundations of a co-operative and unified Europe." You see, he "feels impelled" to write–feels, presumably, that he has something new to say–and yet his words, like cavalry horses answering the bugle, group themselves automatically into the familiar dreary pattern. This invasion of one's mind by ready-made phrases (lay the foundations, achieve a radical transformation) can only be prevented if one is constantly on guard against them, and every such phrase anaesthetizes a portion of one's brain.

I said earlier that the decadence of our language is probably curable. Those who deny this would argue, if they produced an argument at all, that language merely reflects existing social conditions, and that we cannot influence its development by any direct tinkering with words and constructions. So far as the general tone or spirit of a language goes, this may be true, but it is not true in detail. Silly words and expressions have often disappeared, not through any evolutionary process but owing to the conscious action of a minority. Two recent examples were explore every avenue and leave no stone unturned, which were killed by the jeers of a few journalists. There is a long list of flyblown metaphors which could similarly be got rid of if enough people would interest themselves in the job; and it should also be possible to laugh the not un- formation out of existence**, to reduce the amount of Latin and Greek in the average sentence, to drive out foreign phrases and strayed scientific words, and, in general, to make pretentiousness unfashionable. But all these are minor points. The defense of the English language implies more than this, and perhaps it is best to start by saying what it does not imply.

To begin with it has nothing to do with archaism, with the salvaging of obsolete words and turns of speech, or with the setting up of a "standard English" which must never be departed from. On the contrary, it is especially concerned with the scrapping of every word or idiom which has outworn its usefulness. It has nothing to do with correct grammar and syntax, which are of no importance so long as one makes one's meaning clear, or with the avoidance of Americanisms, or with having what is called a "good prose style." On the other hand, it is not concerned with fake simplicity and the attempt to make written English colloquial. Nor does it even imply in every case preferring the Saxon word to the Latin one, though it does imply using the fewest and shortest words that will cover one's meaning. What is above all needed is to let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way around. In prose, the worst thing one can do with words is surrender to them. When you think of a concrete object, you think wordlessly, and then, if you want to describe the thing you have been visualizing you probably hunt about until you find the exact words that seem to fit it. When you think of something abstract you are more inclined to use words from the start, and unless you make a conscious effort to prevent it, the existing dialect will come rushing in and do the job for you, at the expense of blurring or even changing your meaning. Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one's meaning as clear as one can through pictures and sensations. Afterward one can choose–not simply accept– the phrases that will best cover the meaning, and then switch round and decide what impressions one's words are likely to make on another person. This last effort of the mind cuts out all stale or mixed images, all prefabricated phrases, needless repetitions, and humbug and vagueness generally. But one can often be in doubt about the effect of a word or a phrase, and one needs rules that one can rely on when instinct fails. I think the following rules will cover most cases:

(i) Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.These rules sound elementary, and so they are, but they demand a deep change of attitude in anyone who has grown used to writing in the style now fashionable. One could keep all of them and still write bad English, but one could not write the kind of stuff that I quoted in those five specimens at the beginning of this article.

(ii) Never us a long word where a short one will do.

(iii) If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

(iv) Never use the passive where you can use the active.

(v) Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

(vi) Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

I have not here been considering the literary use of language, but merely language as an instrument for expressing and not for concealing or preventing thought. Stuart Chase and others have come near to claiming that all abstract words are meaningless, and have used this as a pretext for advocating a kind of political quietism. Since you don't know what Fascism is, how can you struggle against Fascism? One need not swallow such absurdities as this, but one ought to recognize that the present political chaos is connected with the decay of language, and that one can probably bring about some improvement by starting at the verbal end. If you simplify your English, you are freed from the worst follies of orthodoxy. You cannot speak any of the necessary dialects, and when you make a stupid remark its stupidity will be obvious, even to yourself. Political language–and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists–is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind. One cannot change this all in a moment, but one can at least change one's own habits, and from time to time one can even, if one jeers loudly enough, send some worn-out and useless phrase–some jackboot, Achilles' heel, hotbed, melting pot, acid test, veritable inferno, or other lump of verbal refuse–into the dustbin, where it belongs.

*An interesting illustration of this is the way in which English flower names were in use till very recently are being ousted by Greek ones, Snapdragon becoming antirrhinum, forget-me-not becoming myosotis, etc. It is hard to see any practical reason for this change of fashion: it is probably due to an instinctive turning away from the more homely word and a vague feeling that the Greek word is scientific.

† Example: Comfort's catholicity of perception and image, strangely Whitmanesque in range, almost the exact opposite in aesthetic compulsion, continues to evoke that trembling atmospheric accumulative hinting at a cruel, an inexorably serene timelessness . . .Wrey Gardiner scores by aiming at simple bull's-eyes with precision. Only they are not so simple, and through this contented sadness runs more than the surface bittersweet of resignation." (Poetry Quarterly)

**One can cure oneself of the not un- formation by memorizing this sentence: A not unblack dog was chasing a not unsmall rabbit across a not ungreen field.

Wednesday, 29 December 2010

Quote of the day

I write to escape; to escape poverty.

Edgar Rice Burroughs

Tuesday, 28 December 2010

Quote of the day

It was no wonder that people were so horrible when they started life as children.

Kingsley Amis

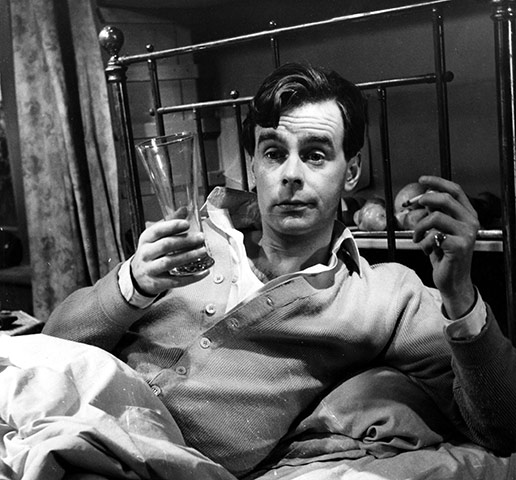

10 of the best

The Guardian looks at the 10 best fictional hangovers and one cure.

My favourite is from Kingsley Amis's Lucky Jim:

My favourite is from Kingsley Amis's Lucky Jim:

Dixon was alive again. Consciousness was upon him before he could get out of the way; not for him the slow, gracious wandering from the halls of sleep, but a summary, forcible ejection. He lay sprawled, too wicked to move, spewed up like a broken spider-crab on the tarry shingle of the morning. The light did him harm, but not as much as looking at things did; he resolved, having done it once, never to move his eyeballs again. A dusty thudding in his head made the scene before him beat like a pulse. His mouth had been used as a latrine by some small creature of the night, and then as its mausoleum. During the night, too, he'd somehow been on a cross-country run and then been expertly beaten up by secret police. He felt bad.He must have been on the Champagne and Guinness again.

Monday, 27 December 2010

Quote of the day

Books to the ceiling,/ Books to the sky,/ My pile of books is a mile high./ How I love them! How I need them!/ I'll have a long beard by the time I read them.

Arnold Lobel

Sunday, 26 December 2010

Saturday, 25 December 2010

Friday, 24 December 2010

Quote of the day

Read in order to live.

Henry Fielding

Thursday, 23 December 2010

Quote of the day

It has yet to be proven that intelligence has any survival value.

Arthur C. Clarke

Tom Jones

Young Bride of Three Hours' standing (just starting on her Wedding Trip). - "Oh, Edwin dear! Here's Tom Jones. Papa told me I wasn't to read it till I was married! The day has come ... at last! Buy it for me, Edwin dear."

Wednesday, 22 December 2010

Quote of the day

Everything I write is designed to be milked to the last drop of revenue.

Leslie Charteris

Tuesday, 21 December 2010

Quote of the Day

The man who writes about himself and his own time is the only man who writes about all people and all time.

George Bernard Shaw

Review: The Proud Robot

"The Proud Robot" (Astounding Science-Fiction, October 1943,) by Lewis Padgett (AKA Henry Kuttner)

Galloway Gallegher is a genius. No, he's a drunk. His subconscious is a genius. The good news is that when Gallegher gets drunk, it releases his subconscious to produce scientific wonders. The bad news is that his subconscious is completely amoral, has no sense of fiscal economy, and when Gallegher comes off a bender he hasn't any memory of what his subconscious has been up to. For example, he may wake up and discover standing in the middle of the room a transparent robot with a screeching voice and a case of narcissism that is usually associated with certain American presidents who affect exotic names.

And in this case, that's exactly what happens.

So far, so weird. You'd think that having to live with a disdainful automaton that does nothing except stare at itself in the mirror would be bad enough, but when Gallegher learns that during a recent beer binge he'd agreed to help a 3D television mogul fight off a rival who is pirating the mogul's programming. Gallegher's day gets worse when he finds out that he's bought a small fortune in diamonds that he used to build the robot, and then that the robot, irritated by the phone calls of the diamond merchant wanting his money, has used hypnosis to impersonate Gallegher and raised the money needed to pay for the diamonds (and not a penny more) by signing away Gallegher's services to the baddie 3D television company for five years. How can Gallegher get the proud robot to cooperate and help him break the bogus contract? How can he stop the bootlegging? And how can he make time with beautiful television star Silver O'Keefe?

"The Proud Robot" is a rarity in science fiction: a genuinely funny short story. The dialogue is droll and the wit is as dry as one of Gallegher's martinis and the plot is farcical with a couple of neat twists at the end. Gallegher is charming and eccentric with the techno-bohemian style of a man who plays with science rather than merely applying it. Joe, as the robot is called, is a frustrating wall of a creature who can't be budged by either reason or threats with a sledgehammer. Even the minor characters are nicely drawn and come across as believable people rather than plot devices.

In recent years, "The Proud Robot" has suffered a lot of criticism from the professionally offended on the grounds that alcoholism is a serious disease and making fun of drinking is wrong. Sorry, the sort of people who get in their knickers in that sort of twist don't say "wrong"; they say "inappropriate." I've never understood the logic behind their anti-alcohol objections because we live in a society where all sorts of ghastly things are made the topic of humour or even the stuff of romantic heroes. If alcohol is off limits, why isn't mental illness? We have fictional heroes who are functional schizophrenics and a couple that are homicidal maniacs.Why aren't they off limits? Or vampires or werewolves? And what about stoner humour? We have an entire sub-genre devoted to drug abuse. How about comedies about people with promiscuous lifestyles? Don't they know that people who sleep around risk everything from emotional abuse to disease to getting shot?

At any rate, "The Proud Robot" is a nice, gentle tale and it's to be enjoyed like meringue, not taken to task because the eggs are loaded with cholesterol.

Now if you will excuse me, I have a Moscow mule to get on the outside of.

Galloway Gallegher is a genius. No, he's a drunk. His subconscious is a genius. The good news is that when Gallegher gets drunk, it releases his subconscious to produce scientific wonders. The bad news is that his subconscious is completely amoral, has no sense of fiscal economy, and when Gallegher comes off a bender he hasn't any memory of what his subconscious has been up to. For example, he may wake up and discover standing in the middle of the room a transparent robot with a screeching voice and a case of narcissism that is usually associated with certain American presidents who affect exotic names.

And in this case, that's exactly what happens.

So far, so weird. You'd think that having to live with a disdainful automaton that does nothing except stare at itself in the mirror would be bad enough, but when Gallegher learns that during a recent beer binge he'd agreed to help a 3D television mogul fight off a rival who is pirating the mogul's programming. Gallegher's day gets worse when he finds out that he's bought a small fortune in diamonds that he used to build the robot, and then that the robot, irritated by the phone calls of the diamond merchant wanting his money, has used hypnosis to impersonate Gallegher and raised the money needed to pay for the diamonds (and not a penny more) by signing away Gallegher's services to the baddie 3D television company for five years. How can Gallegher get the proud robot to cooperate and help him break the bogus contract? How can he stop the bootlegging? And how can he make time with beautiful television star Silver O'Keefe?

"The Proud Robot" is a rarity in science fiction: a genuinely funny short story. The dialogue is droll and the wit is as dry as one of Gallegher's martinis and the plot is farcical with a couple of neat twists at the end. Gallegher is charming and eccentric with the techno-bohemian style of a man who plays with science rather than merely applying it. Joe, as the robot is called, is a frustrating wall of a creature who can't be budged by either reason or threats with a sledgehammer. Even the minor characters are nicely drawn and come across as believable people rather than plot devices.

In recent years, "The Proud Robot" has suffered a lot of criticism from the professionally offended on the grounds that alcoholism is a serious disease and making fun of drinking is wrong. Sorry, the sort of people who get in their knickers in that sort of twist don't say "wrong"; they say "inappropriate." I've never understood the logic behind their anti-alcohol objections because we live in a society where all sorts of ghastly things are made the topic of humour or even the stuff of romantic heroes. If alcohol is off limits, why isn't mental illness? We have fictional heroes who are functional schizophrenics and a couple that are homicidal maniacs.Why aren't they off limits? Or vampires or werewolves? And what about stoner humour? We have an entire sub-genre devoted to drug abuse. How about comedies about people with promiscuous lifestyles? Don't they know that people who sleep around risk everything from emotional abuse to disease to getting shot?

At any rate, "The Proud Robot" is a nice, gentle tale and it's to be enjoyed like meringue, not taken to task because the eggs are loaded with cholesterol.

Now if you will excuse me, I have a Moscow mule to get on the outside of.

Monday, 20 December 2010

Sunday, 19 December 2010

Saturday, 18 December 2010

Friday, 17 December 2010

Quote of the day

There is no incidental music to the dramas of real life.

Sax Rohmer

Review: Black Destroyer

"Black Destroyer" (Astounding Science Fiction, July 1939. Later incorporated into Voyage of the Space Beagle (1950)) was A E Van Vogt's first short story and its making the cover of Astounding says a great deal about the impact that it made. The story is in many ways the dark version of Stanley G Weinbaum's "A Martian Odyssey" (Wonder Stories, July 1934). In both of these, the author set out to produce an alien character that is believable and that, in the end, turns out to be much more memorable than their human counterparts. Both show aliens remarkable abilities and both turn out be members of a dying race that once commanded the heights of civilisation, but where Weinbaum's Tweel is a charming character who becomes friends with the human protagonist, Van Vogt's Coeurl is a heartless killer who lusts over nothing less than mass murder and galactic conquest.

Coeurl is the one of the last remnants of a race that inhabit a distant planet that is the sole satellite of a star thousands of light years from Earth. At the height of their civilisation, the Coeurl (their race and individual names are the same), suffered a sociological disaster that made them question every aspect of their culture to the point where the cohesion of their society broke down and the inhabitants were reduced to criminal barbarism where it was every Coeurl for himself. Once the lords of their planet, the Coeurl are reduced to the status of predators hunting down the few remaining beasts possessing the "id" that they need to survive.

This particular Coeurl is on the edge of despair after realising that he's eaten the last id creature in his territory when a singular thing happens; a giant spaceship from Earth appears in the sky and lands just outside the ruins of the city that the nearly immortal Coeurl abandoned millenia ago.

Coeurl tries to pass himself off to the Earthmen as an animal worthy of study, but his insatiable hunger, criminal nature, and contempt for the primitive visitors exposes him to suspicion after he murders one of the crew. Soon it is a battle of wits as Coeurl keeps the Earthmen guessing while the explorers try to determine the alien's guilt and the extent of its incredible powers.

"Black Destroyer" is an interesting short story for its use of characterisation, but also because of its tremendous influence. It was not only one of the stories that ushered in the Golden Age of science fiction, but its formula of a starship full of motivated, altruistic professionals set the template for everything from Forbidden Planet to Star Trek to Alien. Ironically, this even extends to the way that though Coeurl is vividly written, the Earthmen are little more than vague descriptions tagged to sharp attitudes.

"Black Destroyer" pointed the way toward Van Vogt's uneven career that saw his creative mind struggling with his desire for some sort of neat scientific order to his life. It was a struggle that would produce such sci fi classics as Slan as well as his many obsessions with becoming a self-made superman that would ultimately end up with him enthralled to the hucksterism of Dianetics.

Still, at least we have Coeurl.

Coeurl is the one of the last remnants of a race that inhabit a distant planet that is the sole satellite of a star thousands of light years from Earth. At the height of their civilisation, the Coeurl (their race and individual names are the same), suffered a sociological disaster that made them question every aspect of their culture to the point where the cohesion of their society broke down and the inhabitants were reduced to criminal barbarism where it was every Coeurl for himself. Once the lords of their planet, the Coeurl are reduced to the status of predators hunting down the few remaining beasts possessing the "id" that they need to survive.

This particular Coeurl is on the edge of despair after realising that he's eaten the last id creature in his territory when a singular thing happens; a giant spaceship from Earth appears in the sky and lands just outside the ruins of the city that the nearly immortal Coeurl abandoned millenia ago.

Coeurl tries to pass himself off to the Earthmen as an animal worthy of study, but his insatiable hunger, criminal nature, and contempt for the primitive visitors exposes him to suspicion after he murders one of the crew. Soon it is a battle of wits as Coeurl keeps the Earthmen guessing while the explorers try to determine the alien's guilt and the extent of its incredible powers.

"Black Destroyer" is an interesting short story for its use of characterisation, but also because of its tremendous influence. It was not only one of the stories that ushered in the Golden Age of science fiction, but its formula of a starship full of motivated, altruistic professionals set the template for everything from Forbidden Planet to Star Trek to Alien. Ironically, this even extends to the way that though Coeurl is vividly written, the Earthmen are little more than vague descriptions tagged to sharp attitudes.

"Black Destroyer" pointed the way toward Van Vogt's uneven career that saw his creative mind struggling with his desire for some sort of neat scientific order to his life. It was a struggle that would produce such sci fi classics as Slan as well as his many obsessions with becoming a self-made superman that would ultimately end up with him enthralled to the hucksterism of Dianetics.

Still, at least we have Coeurl.

Thursday, 16 December 2010

Quote of the day