There's a maxim in writing that you should write about what you know. Perhaps a better way to put it is that you shouldn't write about what you don't know. That is, it's more important in writing to avoid showing off your ignorance rather than bragging about your knowledge. The reader expects you to know your subject. You don't have to be the world's greatest expert, but you are expected to do your homework about the bit you're writing about. If you set your story in Tuscany, you should know what Tuscany is like. If it comes across like the Napa Valley with Chianti bottles, you're in trouble. If you're writing an article that opens with a description of someone shaping a bowl on a wood lathe, then you need to know how that's done.

It's simple and obvious advice, but it's amazing how many writers ignore it as they pen scripts set in Bangkok that read suspiciously like atmosphere gleaned from a Thai restaurant in Birmingham.

This idea of writing about what you know is very important because there is one source of knowledge and inspiration that so many writers ignore and that is the source which you (no matter who you are) are most familiar with: Yourself.

I'm not being trite here. The fact of the matter is that the most dramatic, intense, and fascinating stories are ones about the most mundane and everyday experiences. Each of us, if we could see it, lead lives of tremendous drama. I don't mean in the way of some blood-and-thunder adventure or over-egged soap opera. I mean in that if we could see our lives from the outside and if we had the right talent for describing it, our lives would make Hamlet look like a work of limp fan fiction. In fact, if you examine your own life, the people you've met, and the experiences you've had, odds are that if you used them as the starting off point for your writing you'd probably have to tone them down rather than jazz them up. Fiction is much easier to roll out because fiction must be believable.

I'm not arguing here for autobiography, but I am arguing that if you want your writing to really work you should, no matter how fantastic or epic the subject matter, look at it from the human dimension because that it where the real drama is played out. The trick is to be able to describe it properly. Look at the best stories, the ones that really work, and you'll find that it's what happens at that level that makes them work. The funniest comedies often revolve around someone trying to ride out a moment of embarrassment. The most intense suspense is two men in a train compartment; one of whom knows a secret. The most poignant love affairs are the ones where nothing happens. And the greatest struggle is the one we all face as we go through our daily lies toward an future wrapped in fog. It is in the intimate and the personal that the best stories occur.

I think that's one of the reasons why television dramas, especially in Britain, have fallen so badly in the past twenty years. In the old days, the primitive nature of technology and the low budgets of the producers meant that television scripts had to work under tight restrictions. Programmes had to be shot quickly, in the studio, often with video cameras, little or no editing, and not much in the way of effects. That meant that the stories had to be intimate, almost claustrophobic ones that dealt with realistic characters and plots carried along by dialogue. Today? The effects and flashy editing is all very nice, but it means that the programmes are carried along by images and music while the stories revolve around emotionally stunted creatures who wouldn't last five minutes in real life.

But that is a topic that I'll deal with properly another day.

Thursday, 30 September 2010

Wednesday, 29 September 2010

Quote of the day

The most essential educational product is Imagination.

G K Chesterton

The critic's dilemma

Whether it's books,plays, film, or television, writing reviews is great fun. Not only do you have an ironclad excuse to put your feet with a novel, you get share your opinions about it with others in a way that doesn't involve cornering hapless victims If you're lucky, you might even find a market for your critiques and actually get paid for gassing on about how wretched Michael Bay's editing is. If you're really lucky you'll become an influential critic who guides public tastes. Then with mere taps of the keyboard you'll be able to destroy careers, blacken reputations, plight lives, and drive honest struggling artists into the arms poverty, despair and suicide.

Yeah, I'm tellin' ya. Good times.

But reviewing isn't all comps and free advance copies. There are pitfalls as well and not all of them involve being on the lookout for infuriated authors brandishing horsewhips. The main one is when the critic's strength becomes a weakness.

In order to review competently, the critic must be familiar with his subject. This is because reviewing is more than conveying the critic's impressions of a work. The reviewer goes a step further by bringing to the table an expert knowledge of what he's discussing. He hasn't seen a few movies, he's seen thousands. He hasn't read a couple of novels in a particular genre, he's swept the shelves. And that viewing and reading wasn't passive. It was done with an informed eye that understands the medium, the genre, the topics, the technique, and the business so that he has an intimate understanding of what works and what doesn't and why.

Here's where the paradox comes in. All this knowledge and experience provides the critic with a privileged insight into the work in question. Unfortunately, it can also act as a barrier. Reviewers who have read everything under sun regarding a particular genre might be experts on it, but they also run the risk of becoming jaded experts. They may forget the innocent pleasure of killing a rainy afternoon by popping in a video or curling up with a good book. They may not be able to appreciate that the average audience member may not have seen every single variation of a romantic comedy and have not become blasé about them. It's the sort of mindset that begins to crave novelty for its own sake and if you aren't careful you'll end up becoming the sort of reviewer who gives two thumbs up to turgid, unwatchable arthouse pictures because they're "different" or praises "Poona the **** Dog" because it has an obscene title.

Another danger of the over-informed critic is that the reviewer may become obsessed with theory or technique and everything else is lost to view. It's easy to forget that the mechanics of putting a story together are a means to an end rather than an end in themselves. A film or novel or teleplay that exists solely as a showcase of technique belong in a classroom, not running about loose among the general public. A review that bangs on about stunning technique in a boring story would commend a toolbox for its tools.

Theory can be an equally sticky trap. Literary or film theory has its place, but if a reviewer gets to obsessed with theory, it becomes a masonic handshake; a way of separating the bourgeois outsiders from the in-the-know club members. "You find this piece incomprehensible? Then clearly you aren't au fait with Gendensky's post-modern modernism of the subjective ironic" isn't a review, it's a membership card. Theory should be used to illuminate a work, not act as a secret decoder ring to make it comprehensible to the select.

Finally, there is the danger of familiarity breeding contempt or worse, having just the contempt in the first place. The worst reviews possible are those written by someone who hates the genre under discussion. This could be codified as the Critic's First Law: Never review a genre that you have no liking for. There was once a Seattle-based theatre critic who despised Shakespeare and every time he had to review a production of the bard his copy was 75 percent sullen grumbling about how much he hated the playwright and all his works. Needless to say, his reviews were never helpful nor interesting.

I don't except myself from this rule. I, for example, cannot abide modern vampire stories and I only bought a secondhand copy of the Twilight DVD because I love how well the Rifftrax boys eviscerated it in one word (Llllllllllllllllllladies!). For that reason, I'd be a very poor person to review the genre. Subject it to vitriolic rants, yes; reviews, no.

However, don't get the idea that I'm saying that you shouldn't review works you hate. I'm referring to genres or mediums, not individual titles. If you loathe a particular book or television series, go to town on it; draw blood, take no prisoners. If you can save one person from wasting the price of a ticket or an evening's reading time, then it's all worth it.

Yeah, I'm tellin' ya. Good times.

But reviewing isn't all comps and free advance copies. There are pitfalls as well and not all of them involve being on the lookout for infuriated authors brandishing horsewhips. The main one is when the critic's strength becomes a weakness.

In order to review competently, the critic must be familiar with his subject. This is because reviewing is more than conveying the critic's impressions of a work. The reviewer goes a step further by bringing to the table an expert knowledge of what he's discussing. He hasn't seen a few movies, he's seen thousands. He hasn't read a couple of novels in a particular genre, he's swept the shelves. And that viewing and reading wasn't passive. It was done with an informed eye that understands the medium, the genre, the topics, the technique, and the business so that he has an intimate understanding of what works and what doesn't and why.

Here's where the paradox comes in. All this knowledge and experience provides the critic with a privileged insight into the work in question. Unfortunately, it can also act as a barrier. Reviewers who have read everything under sun regarding a particular genre might be experts on it, but they also run the risk of becoming jaded experts. They may forget the innocent pleasure of killing a rainy afternoon by popping in a video or curling up with a good book. They may not be able to appreciate that the average audience member may not have seen every single variation of a romantic comedy and have not become blasé about them. It's the sort of mindset that begins to crave novelty for its own sake and if you aren't careful you'll end up becoming the sort of reviewer who gives two thumbs up to turgid, unwatchable arthouse pictures because they're "different" or praises "Poona the **** Dog" because it has an obscene title.

Another danger of the over-informed critic is that the reviewer may become obsessed with theory or technique and everything else is lost to view. It's easy to forget that the mechanics of putting a story together are a means to an end rather than an end in themselves. A film or novel or teleplay that exists solely as a showcase of technique belong in a classroom, not running about loose among the general public. A review that bangs on about stunning technique in a boring story would commend a toolbox for its tools.

Theory can be an equally sticky trap. Literary or film theory has its place, but if a reviewer gets to obsessed with theory, it becomes a masonic handshake; a way of separating the bourgeois outsiders from the in-the-know club members. "You find this piece incomprehensible? Then clearly you aren't au fait with Gendensky's post-modern modernism of the subjective ironic" isn't a review, it's a membership card. Theory should be used to illuminate a work, not act as a secret decoder ring to make it comprehensible to the select.

Finally, there is the danger of familiarity breeding contempt or worse, having just the contempt in the first place. The worst reviews possible are those written by someone who hates the genre under discussion. This could be codified as the Critic's First Law: Never review a genre that you have no liking for. There was once a Seattle-based theatre critic who despised Shakespeare and every time he had to review a production of the bard his copy was 75 percent sullen grumbling about how much he hated the playwright and all his works. Needless to say, his reviews were never helpful nor interesting.

I don't except myself from this rule. I, for example, cannot abide modern vampire stories and I only bought a secondhand copy of the Twilight DVD because I love how well the Rifftrax boys eviscerated it in one word (Llllllllllllllllllladies!). For that reason, I'd be a very poor person to review the genre. Subject it to vitriolic rants, yes; reviews, no.

However, don't get the idea that I'm saying that you shouldn't review works you hate. I'm referring to genres or mediums, not individual titles. If you loathe a particular book or television series, go to town on it; draw blood, take no prisoners. If you can save one person from wasting the price of a ticket or an evening's reading time, then it's all worth it.

Tuesday, 28 September 2010

Quote of the day

There are two motives for reading a book: one, that you enjoy it; the other, that you can boast about it.

Bertrand Russell

Monday, 27 September 2010

Quote of the day

To be great is to be misunderstood.Ralph Waldo Emerson

Spelling is importent

If I mention spelling to aspiring writers, they're likely to look at me as if I'm telling them to go back to grammar school. Odds are, I probably am, but that doesn't change the fact the spelling is one of those skills that a writer must master to avoid being dismissed after the first sentence. There are a lot of rules that you can break as a writer, You can be ungrammatical, dispense with linear narrative, make up your own personal quotation marks, fire commas at a page as if from a shotgun, and write like J K Rowling and get away with it, but if you can't spell, you might as well switch to playing the bassoon.

But surely in this digital age needing to spell is a bit like needing to know how to skin a bear with a pen knife. True, things like spell check and grammar check can make writing and editing easier. You can just whiz along; pounding out words on the screen without having to keep glancing at a cheat sheet loaded with cautions about I before E or the proper use of the pluperfect subjunctive. If you're a good citizen of Oceania and don't want to inadvertently commit thoughtcrime, you can even set your word processing software to flag any un-PC words, so all your output will be in doubleplus good Newspeak. However, these editing tools are just that; tools. There purpose is to help make the job of proofing your text easier. They're no substitute for a keen eye and solid judgment.

One problem to look out for is homonyms. Spell check can catch a word that isn't in its dictionary, but it has a problem with words that sound the same but are spelled differently. Threw and through, to and too, bough and bow; each of these get by the machine, but they shouldn't get past the eye. It's an error that is particularly telling because its so common, which I should have spelled as "it's so common". A slip of the keyboard and "quiet" becomes "quite"; so easy to do, yet impossible for the machine to catch.

Then there's malapropisms, which are words that sound enough like the correct one that it slips by both the writer and the computer, such as,

I thought it was bad enough that their cars were built the wrong way 'round.

One final point, don't think that just because you're writing a very short piece that you don't need to worry about spelling. Even the shortest bit of text needs proofing, as the example below proves:

But surely in this digital age needing to spell is a bit like needing to know how to skin a bear with a pen knife. True, things like spell check and grammar check can make writing and editing easier. You can just whiz along; pounding out words on the screen without having to keep glancing at a cheat sheet loaded with cautions about I before E or the proper use of the pluperfect subjunctive. If you're a good citizen of Oceania and don't want to inadvertently commit thoughtcrime, you can even set your word processing software to flag any un-PC words, so all your output will be in doubleplus good Newspeak. However, these editing tools are just that; tools. There purpose is to help make the job of proofing your text easier. They're no substitute for a keen eye and solid judgment.

One problem to look out for is homonyms. Spell check can catch a word that isn't in its dictionary, but it has a problem with words that sound the same but are spelled differently. Threw and through, to and too, bough and bow; each of these get by the machine, but they shouldn't get past the eye. It's an error that is particularly telling because its so common, which I should have spelled as "it's so common". A slip of the keyboard and "quiet" becomes "quite"; so easy to do, yet impossible for the machine to catch.

Then there's malapropisms, which are words that sound enough like the correct one that it slips by both the writer and the computer, such as,

We heard the ocean is infatuated with sharksFinally, there are differences in spellings between dialects. Americans, it's well known, have a notorious problem with spelling, what with "color" for "colour" and "recognize" for "recognise" and, unfortunately, many spell check software packages are written by Americans, so a writer in Britain and other parts of the civilised world must spellcheck the spell check.

I thought it was bad enough that their cars were built the wrong way 'round.

One final point, don't think that just because you're writing a very short piece that you don't need to worry about spelling. Even the shortest bit of text needs proofing, as the example below proves:

Marcel Proust

Having trouble keeping up with your Marcel Proust?

Allow us to summarise it for you.

Sunday, 26 September 2010

Quote of the day

By a curious confusion, many modern critics have passed from the proposition that a masterpiece may be unpopular to the other proposition that unless it is unpopular it cannot be a masterpiece.

G. K. Chesterton

Saturday, 25 September 2010

Friday, 24 September 2010

Quote of the day

At the present rate of progress, it is almost impossible to imagine any technical feat that cannot be achieved - if it can be achieved at all - within the next few hundred years.

Sir Arthur C. Clarke

Review: Solaris

We think of the world as an ordered place that operates according to immutable laws. By studying the world, we believe that we can discover these laws and through them understand exactly how the world works, its history, and its future. This is based, in part, on the assumption that our reason maps onto the order of the universe. We assume that our logic, our mathematics, or models, our categories, and all the other things that we use to make sense of what we observe is reflected in objective reality. If it doesn't, then it merely means that we've made an error that will eventually be corrected.

We think of the world as an ordered place that operates according to immutable laws. By studying the world, we believe that we can discover these laws and through them understand exactly how the world works, its history, and its future. This is based, in part, on the assumption that our reason maps onto the order of the universe. We assume that our logic, our mathematics, or models, our categories, and all the other things that we use to make sense of what we observe is reflected in objective reality. If it doesn't, then it merely means that we've made an error that will eventually be corrected.That is one of the reasons we believe that if we ever encounter an extraterrestrial civilisation we'll be able to communicate it because our reason and theirs must meet in objective reality.

But what would happen if man encountered something totally alien; something with which we share no common ground and appears to violate the laws of nature as a matter of course? That's the question posed by Stanislaw Lem's 1961 science fiction novel Solaris.

Solaris is the name of both a planet circling a pair of binary stars in the constellation of Aquarius and the planet's sole inhabitant. The confusion is understandable because the inhabitant is a living ocean that covers most of the planet's surface. For about a century, Earthmen have been studying Solaris and in all that time have learned almost nothing definite about it. It violates every law of physics, chemistry, and logic. It doesn't even possess an atomic structure and is composed of some new form of matter that is alien right down to the subatomic level. Solaris is definitely alive, but whether it is intelligent or not is unknown because after decades of intense effort all attempts to communicate with the creature have failed completely.

The base of operations for the study of Solaris is a station that floats via anti-gravity above the ever-changing surface of Solaris. Kris Kelvin, a psychologist, arrives on the station and discovers that the place is a shambles; that one of the three crewmen has committed suicide and the other two have locked themselves in their quarters and refuse to come out. Kelvin finds that after an attempt to provoke a reaction in Solaris by blasting it with radiation the living ocean has responded by sending "visitors" to the station that are driving the crew insane. The crew refuse to explain what is going on, but Kelvin soon learns for himself when his wife Rhyea, who killed herself ten years ago, appears out of nowhere. However, this Rhyea never eats, can smash her way through steel doors, come back to life after drinking liquid oxygen, and when she's accidentally blown off the station in a shuttle capsule to certain death she returns in a few hours as if nothing had happened.

Is this an attack? An attempt to communicate? Or are Kelvin and the others just going mad?

Adapted for the screen in the USSR in 1972 and again by Hollywood in 2002, Solaris is best known today by art house crowds who flocked to the "Soviet 2001" and stayed away in droves from the remake. If you've seen either of these, however, you've not seen Solaris because Lem despised both versions as missing the point of the book. Both film versions concentrated on the tragic love story of Kelvin and Rhyea and expanded it until Solaris itself is relegated to an easily forgotten off-screen presence.

However, in the novel the romance is merely a subplot to humanise the much more important story of mankind's increasing frustration with trying to understand and contact this hopelessly alien creature. For Lem, Solaris is a story of ideas and atmosphere revolving about this unsolvable enigma that throws down the gauntlet to modern, secular man's greatest conceit; that his science can know all. The Earthmen are faced with an impossible crisis: Try to contact an alien intelligence (if it is intelligent) with which they can have no common ground or accept defeat by admitting that the universe is a chaotic place beyond human understanding, our science is merely a child's comforting delusion, and that the only god possible is a frustrated, unfinished one.

Much of Solaris has a powerful poetic feel to it as Lem describes in detail the bizarre phenomena exhibited by the creature as it creates weird abstract shapes the size of mountains one moment and then what look like giant plaster gardens complete with tools the next. He counterpoises these often beautiful descriptive passages with long discourses on the various theories and attempts by scientists to explain what is happening and failing utterly. Though effective, sometimes these passages go on a bit too far, which is very easy when the author himself admits that what he's relating is the inexplicable and the pointless. However, unlike the films, the novel moves along at a brisk pace and has none of the indulgences of the cinematic incarnations, such as a drive into the city that takes what seems like a week or trying to turn a science fiction story into a cut-rate M. Night Shyamalan shaggy dog story.

Neither Campellian adventure story nor pretentious new wave rubbish, Solaris demonstrates how intelligent, adult science fiction can be written and why Stanislaw Lem counts as among the best of the Eastern European Sci Fi writers of the Cold War era.

Thursday, 23 September 2010

Quote of the day

Another unsettling element in modern art is that common symptom of immaturity, the dread of doing what has been done before.Edith Wharton

Creating believable characters

The way to create compelling, believable characters that will stick in your reader's minds long after the plot has faded into oblivion is to have something to say. If you have a compelling story, your characters will be compelling. You won't be able to help yourself. As cometh the hour, cometh the man, so too cometh the plot, cometh the characters. If your story is going right (and if you're honest with yourself), you'll see which characters are working, which aren't, and which should just be chucked in the bin.

That being said, that are things you can do to make handling your characters easier. Ask yourself, what sort of character does your story need? What is his purpose? How complex should he be. One complaint about many stories is that the characters are "wooden". This is a legitimate criticism and I've read many a story that felt like a trip to the lumber yard, but that isn't always the case. Some plots require very complex characters with deep inner lives and rich histories to make everything come alive. When we read something like Charles Dickens novel it's the characters we remember much more than this or that turn of the plot. Other stories, however, actually beg for a bit of termite fodder. Most science fiction, for example, leans very heavily on ideas and invoking a sense of wonder. More often what the author is interested in is what the character sees rather than who he is. A three-dimensional person becomes an actual liability in such a situation because he comes off rather like that twit who insists in standing smack in front of the Monet, so you can't get a decent view.

That said, it isn't an excuse for, as James Hilton wrote, creating a dummy and and hanging labels on it. I love the old Doc Savage novels with all their simple blood and thunder, but it amazes me how Kenneth Robeson (in his various incarnations) would time and again roll out some member of the cast who was little more than a few attitudes and adjectives–and I mean main characters. They weren't beloved characters; they were catch phrases and quirks wrapped up in descriptions.

Another thing to keep in mind is that the reader must care about your character. You may want to create the ultimate anti-hero, for example, but you can't make him utterly unsympathetic. You have to give the reader some reason to like him on some level and to root for him. Sure, he's a misogynistic, violent, unhygienic, uncouth cad, but maybe he's witty or smart or says things the reader would love to but never dares. Maybe he's the underdog. Maybe his enemy is infinitely worse by comparison. At any rate, your characters must appeal.

The same thing goes for sympathetic characters. Your heroine may be as lovable as the day is long, but don't assume that because she is lovable your readers will love her. Give them a reason; earn their affection. Show them why she is lovable by her words, her actions, and how other people react to her. If you borrow against what you assume is some demanded affection, then you're falling into mere sentimentality and manipulation.

But where do good characters come from? Ideally, they should spring from the plot and then the plot from them until an artistic Worm Oroboros appears, but there are other ways to get started. One of the simplest and easiest ways is to borrow from what you've read. By that I do not mean lifting characters whole from another work and passing them off as your own under a ginger wig and an assumed name. At best, you'll end up with a pastiche that is about as satisfying as a souffle reheated in the microwave or at worst, you'll descend into the artistic cul-de-sac of fan fiction and TV spin-off novels.

You can, however, use an existing character as a starting model for your own. that means taking traits or motives from various characters and recombining them to create something new. Maybe you want a character who's as charmingly befuddled as Father Brown, yet as coldly deadly as James Bond. Perhaps you want the insular romanticism of a Jane Austen protagonist mixed with the cosmic dread of a Lovecraft narrator. Maybe you want Conan the Barbarian via Bertie Wooster; there are all sorts of possibilities if you can piece the right parts together.

The most fruitful source for characters is real life. Many people believe that the talent of a writer is the ability to put words on paper. In fact, it's really the ability to observe and to shamelessly exploit what they've seen. Perhaps the best effort I've made at characterisation was a play I based on a collection of acting friends. If nothing else, it made the play very easy to cast. By taking the traits of my friends, exaggerating some, inverting others, and sometimes combining two people into one, I soon had a troupe of characters that were the most lifelike I'd ever managed. Curiously, when it came to actually producing the play the only character I had trouble with casting was the one based on me.

I wasn't at all suitable for the role.

That being said, that are things you can do to make handling your characters easier. Ask yourself, what sort of character does your story need? What is his purpose? How complex should he be. One complaint about many stories is that the characters are "wooden". This is a legitimate criticism and I've read many a story that felt like a trip to the lumber yard, but that isn't always the case. Some plots require very complex characters with deep inner lives and rich histories to make everything come alive. When we read something like Charles Dickens novel it's the characters we remember much more than this or that turn of the plot. Other stories, however, actually beg for a bit of termite fodder. Most science fiction, for example, leans very heavily on ideas and invoking a sense of wonder. More often what the author is interested in is what the character sees rather than who he is. A three-dimensional person becomes an actual liability in such a situation because he comes off rather like that twit who insists in standing smack in front of the Monet, so you can't get a decent view.

That said, it isn't an excuse for, as James Hilton wrote, creating a dummy and and hanging labels on it. I love the old Doc Savage novels with all their simple blood and thunder, but it amazes me how Kenneth Robeson (in his various incarnations) would time and again roll out some member of the cast who was little more than a few attitudes and adjectives–and I mean main characters. They weren't beloved characters; they were catch phrases and quirks wrapped up in descriptions.

Another thing to keep in mind is that the reader must care about your character. You may want to create the ultimate anti-hero, for example, but you can't make him utterly unsympathetic. You have to give the reader some reason to like him on some level and to root for him. Sure, he's a misogynistic, violent, unhygienic, uncouth cad, but maybe he's witty or smart or says things the reader would love to but never dares. Maybe he's the underdog. Maybe his enemy is infinitely worse by comparison. At any rate, your characters must appeal.

The same thing goes for sympathetic characters. Your heroine may be as lovable as the day is long, but don't assume that because she is lovable your readers will love her. Give them a reason; earn their affection. Show them why she is lovable by her words, her actions, and how other people react to her. If you borrow against what you assume is some demanded affection, then you're falling into mere sentimentality and manipulation.

But where do good characters come from? Ideally, they should spring from the plot and then the plot from them until an artistic Worm Oroboros appears, but there are other ways to get started. One of the simplest and easiest ways is to borrow from what you've read. By that I do not mean lifting characters whole from another work and passing them off as your own under a ginger wig and an assumed name. At best, you'll end up with a pastiche that is about as satisfying as a souffle reheated in the microwave or at worst, you'll descend into the artistic cul-de-sac of fan fiction and TV spin-off novels.

You can, however, use an existing character as a starting model for your own. that means taking traits or motives from various characters and recombining them to create something new. Maybe you want a character who's as charmingly befuddled as Father Brown, yet as coldly deadly as James Bond. Perhaps you want the insular romanticism of a Jane Austen protagonist mixed with the cosmic dread of a Lovecraft narrator. Maybe you want Conan the Barbarian via Bertie Wooster; there are all sorts of possibilities if you can piece the right parts together.

The most fruitful source for characters is real life. Many people believe that the talent of a writer is the ability to put words on paper. In fact, it's really the ability to observe and to shamelessly exploit what they've seen. Perhaps the best effort I've made at characterisation was a play I based on a collection of acting friends. If nothing else, it made the play very easy to cast. By taking the traits of my friends, exaggerating some, inverting others, and sometimes combining two people into one, I soon had a troupe of characters that were the most lifelike I'd ever managed. Curiously, when it came to actually producing the play the only character I had trouble with casting was the one based on me.

I wasn't at all suitable for the role.

Wednesday, 22 September 2010

Quote of the day

Being a woman is a terribly difficult task since it consists principally in dealing with men.

Joseph Conrad

Tuesday, 21 September 2010

Quote of the day

Critics search for ages for the wrong word, which, to give them credit, they eventually find.Peter Ustinov

Review: Invasion of the Body Snatchers

In 1956, Hollywood set loose a film that defined an era–though what exactly it defined is open to interpretation. Invasion of the Body Snatchers is either a paranoid screed against the Red Menace or a paranoid screed against McCarthyism. Or it's a reasoned indictment of one or the other. Or a warning about the threat espoused by one or the other. It gets confusing. At any rate, this was the film that established the concept of pod people in the public imagination along with the image of a distraught Kevin McCarthy stumbling in the middle of a California motorway shouting, "You're next! YOU'RE NEXT!!"

In 1956, Hollywood set loose a film that defined an era–though what exactly it defined is open to interpretation. Invasion of the Body Snatchers is either a paranoid screed against the Red Menace or a paranoid screed against McCarthyism. Or it's a reasoned indictment of one or the other. Or a warning about the threat espoused by one or the other. It gets confusing. At any rate, this was the film that established the concept of pod people in the public imagination along with the image of a distraught Kevin McCarthy stumbling in the middle of a California motorway shouting, "You're next! YOU'RE NEXT!!"Invasion of the Body Snatchers went on to become a classic of American cinema that was remade three times, ripped off too often to count, and gave the first logical explanation of why people in Minnesota act the way they do. Unfortunately, like many films, it has tended to overshadow the book upon which it was based; so much so that the latter had to change its title from The Body Snatchers to match its cinematic offspring.

If you've seen the film, The Body Snatchers (1954) by Jack Finney comes as a surprise. Even though the plot is basically the same, the approach is very different. Both recount the tale of Dr Miles Bennell, a physician in the small California town of Mill Valley (Santa Mira in the film). It's a quiet place off the main highway, but one with an increasingly menacing undertone as Dr Bennell is faced with a parade of patients claiming that their friends and relatives have been replaced by impostors. Dismissing it at first as some sort of mass hysteria, Bennell and a few of his friends piece together clues that lead them to the conclusion that the inhabitants of the town are being replaced by replicas generated by alien plants from outer space. If something isn't done, the town and eventually the entire human race will be replaced by the invaders

So far, so frightening, but where director Don Siegel emphasised the horror aspects of the plot, Finney took a more poetic tack. Siegel's invaders are marked by an ever mounting air of calculated menace as they gain the upper hand as more and more of the humans are disposed of. The invaders speak with loving relish at the opportunity of winning over another unwilling convert to their cause. In Finney's version, the alien invasion results in a stultifying effect on the community. Finney's replicas aren't fanatics, they're emotionless drones that spread like brambles that smother the native population. In the film, the replicants are monsters ever on the hunt for the Other. In the book, their increasing grasp is seen in the frustrations of salesmen who can't get the townsmen to buy anything except staples and restaurateurs who sit staring gloomily at empty dining rooms.

Eventually, we learn that the aliens are less conquers than nihilists. They don't want to possess the Earth; they merely wish to propagate themselves. This isn't good for mankind because their propagation involves eliminating competing lifeforms and that means every living thing on the planet. The replicas aren't intended to take over our way of life. They will merely die within five years, leaving Earth a lifeless world that the aliens will abandon. In a way, it's a rather despondent war.

Finney's novel is much more literary that the screenplay. It doesn't make you jump up and spill your popcorn the way the film does, but the horror of the situation is much deeper because you understand it better. The writing is smooth and draws the reader along, but it can't cover the holes that Finney fails to fill or the fact that his protagonists have a maddening tendency to ignore vital plot points simply because it would be inconvenient for Finney to explore them at that time. The other place where Finney doesn't match up to the film is that in the film, Dr Bennell is faced with real menace as he learns that he is the only human left in the town whereas in the book he discovers that many other people have survived the peril, which diffuses the drama.

In all, I would say that the book wins out in terms of style and a thoughtful plot that in some ways is as much an attack on Freud as anything else, but the film scores points for sheer impact. The nice thing is that this isn't a competition, so we can enjoy both on their merits.

Monday, 20 September 2010

Review: Pyramids

Teppic is a young man with a problem. He's just finished the tortuous (and often fatal) final exam that completes his training at Ankh-Morpork's Assassin's Guild when his father dies unexpectedly after trying to fly off a balcony. That would be merely tragic except that Teppic's late father was King Teppicymon XXVII of the ancient land of Djelibeybi and Teppic discovers that being an assassin is no preparation for his new career as a sort of living god. Worse, he has to make sure his father is properly buried and that means building an extremely large and expensive pyramid for him. Still worse, the late Teppicymon XXVII, whose ghost is still hanging around, is not taking too kindly with his body being mummified and he definitely doesn't want to be interred inside several hundred thousand tons of black marble.

Teppic is a young man with a problem. He's just finished the tortuous (and often fatal) final exam that completes his training at Ankh-Morpork's Assassin's Guild when his father dies unexpectedly after trying to fly off a balcony. That would be merely tragic except that Teppic's late father was King Teppicymon XXVII of the ancient land of Djelibeybi and Teppic discovers that being an assassin is no preparation for his new career as a sort of living god. Worse, he has to make sure his father is properly buried and that means building an extremely large and expensive pyramid for him. Still worse, the late Teppicymon XXVII, whose ghost is still hanging around, is not taking too kindly with his body being mummified and he definitely doesn't want to be interred inside several hundred thousand tons of black marble.And if that isn't bad enough, the greatest mathematician on the Discworld is a camel.

Pyramids (2001) is another in Terry Pratchett's prolific Discworld series. One reason why the stories have remained so popular after over a quarter of a century is that Pratchett has turned his turtle-borne planet into a personal sub-genre where almost anything can happen. In this instance, the action is diverted away from the usual location and characters of Ankh-Morpork in favour of the Discworld's version of Ancient Egypt. Djelibeybi is a country 150 miles long and two miles wide. It is so old that its neighbours treat it with great respect despite the fact that kings of Djelibeybi have bankrupted the nation with their mania for building ever larger pyramids. It's also so steeped in tradition that "hide-bound" doesn't begin to cover it. Djelibeybi is a plae where time literally stands still–in fact, it's running in place. Teppic soon discovers that as king he really can't do much of anything because everything is covered by some long-established rule or other and before he can open his mouth the ancient high priest Dios is rattling off Teppic's decisions for him.

Pratchett is in fine form here with all manner of word play and asides that make Pyramids a slow read because of the temptation to reread every other paragraph. There's also an audaciousness as he dares to bring in such absurdities as a literally lost kingdom, time-looping contractors, a pantheon of gods fighting over who gets to move the sun across the sky, and embalmers who have to cope with customers who rise out of their sarcophagi to compliment him on his workmanship. It's almost as if Pratchett regards suspension of disbelief as a challenge and he wants to see if he can stretch it to breaking point.

However, unlike some of the more ambitious Discworld novels, Pyramids is very straightforward in its plot–which is saying something for a story where Teppic turns around and discovers that his kingdom isn't where he left it. The social satire is mild compared to likes of Thud or Monstrous Regiment and some characters, such as the handmaiden Ptraci aren't developed as well as they could be. It's more of a flat-out romp where no one suffers anything worse than being eaten by a crocodile and all's well that ends more or less well for most of the protagonists.

All in all, not in the mainstream of the series, nor the most memorable, but a lot of fun.

Sunday, 19 September 2010

Saturday, 18 September 2010

At the Earth's Core

Enjoy.

Friday, 17 September 2010

Quote of the day

It's a poor sort of memory that only works backward.Lewis Carroll

Thursday, 16 September 2010

Wednesday, 15 September 2010

Quote of the day

A good novel tells us the truth about its hero but a bad novel tells us the truth about its author.G K Chesterton

Tuesday, 14 September 2010

Monday, 13 September 2010

Notable notebooks

Last July I talked about how important notebooks are for writers. Now The Art of Manliness looks at famous men and what they jotted down their odd thoughts in.

F Gwynplaine MacIntyre

The New York Times looks at the bizarre life and even more bizarre death of F Gwynplaine MacIntyre; a science fiction writer whose own life was a work of fiction.

Some people think that writers are mad–that's because some are.

Some people think that writers are mad–that's because some are.

Ayn Rand interview (part 1 of 3)

I'm currently ploughing through Atlas Shrugged because the blogs keep mentioning it, so I figure this 1959 interview needs a re-airing.

Sunday, 12 September 2010

Quote of the day

The right word may be effective, but no word was ever as effective as a rightly timed pause.Mark Twain

Friday, 10 September 2010

Review: The Girl with the Hungry Eyes

Vampires have never been more popular–a statement that is pretty frightening when you think about it. They seem to be everywhere. Go to any book stall and your bound to find a shelf groaning under the weight of vampire novels. Vampire films infest the marquees of cinemas around the world. Teenage girls moon after sparkly vampires. Older girls watch cable programmes about soft-core pornographic vampires. Graphic novels (comic books to anyone over forty) have more than their share. There are even would-be vampires who discover that imitating the fictional variety is a good way to end up in prison or the asylum.

Vampires have never been more popular–a statement that is pretty frightening when you think about it. They seem to be everywhere. Go to any book stall and your bound to find a shelf groaning under the weight of vampire novels. Vampire films infest the marquees of cinemas around the world. Teenage girls moon after sparkly vampires. Older girls watch cable programmes about soft-core pornographic vampires. Graphic novels (comic books to anyone over forty) have more than their share. There are even would-be vampires who discover that imitating the fictional variety is a good way to end up in prison or the asylum.Vampire detectives, vampire spies, vampire armies, vampire clans, vampire waitresses, vampire this that and the other; the only thing we don't see nowadays is the vampire vampire. It's a paradox. Modern society seems dead set on ringing every change out of the vampires. They've been portrayed as suave sophisticates, mindless zombies, exotic lovers, remorseless psychopaths, calculating gangsters, disaffected flatmates, stand-ins for"alternative lifestyles", and as safe, sparkly teenage love interests that make one suspect that vampire is a euphemism for gay boyfriend. Yet in all of this, what is lost is the essence of what the vampire is; what makes him terrifying and uncanny.

Most vampire fiction of the past few years has focused on the more materialistic aspects of the creature. A vampire drinks blood, which is portrayed as an unpleasant, but necessary diet. A vampire is vulnerable to certain things like stakes and sunlight, but it's on the same level as Superman and kryptonite. A vampire is immensely strong, can climb walls, and, last but most emphatically not least, the vampire is so sexually attractive that he makes Rudolph Valentino look like a dead pope. All well and good, but what is often ignored is that the vampire is a supernatural being; an animated corpse with a trapped, tormented soul that is possessed by a demon that feeds on the living. It is a creature that lives, for want of a better word, for the sole purpose of corrupting and destroying mortals. Modern writers often forget that Bram Stoker's Dracula was a stand-in for Satan himself and played a similar role in the story. Put it simply, vampires are monsters.

Blood is a perfect illustration of this. For the classic vampire, feeding off of blood isn't like a human being sitting down to a plate of chops. A vampire would never be satisfied with a blood substitute as in the Sookie Stackhouse novels, nor would it get any nourishment from hunting deer as in the Twilight series. Blood for the classic vampire is the conveyor of something much more fundamental and essential to the vampire. Blood is life itself. That is what the vampire feeds on and that is what makes it so frightening. It doesn't want a very runny black pudding. It wants to eat your soul.

This literal soul-sucking is best described in Fritz Leiber's sideways vampire short story "The Girl with the Hungry Eyes" (1949). The vampire here is a mysterious, nameless woman known as "The Girl". She's a professional model who has become a wild sensation across the country. Never smiling and with a strange hunger in her eyes, she stares out of billboards, magazines, and advertisements by the thousands, yet no one has ever seen her in person except for the photographer who snaps her picture and he wishes that he'd never met her. She shows up one evening at his studio and despite having zero experience as a model and impossible demands for anonymity, the cameraman's clients are soon falling over themselves to hire her.

The Girl is an unnerving character. She is utterly aloof, reveals nothing about her past, and when she talks to the photographer it's in a condescending tone that one would expect of a diner who granted an audience to the lobster he'd chosen from the restaurant tank. Our hero can't make up his mind whether he's attracted or frightened by her. And then the murders start as seemingly healthy men with no connection to one another are found dead around the city. He eventually comes to realise that she isn't exactly human. Indeed, she may not exist in any sense that he could understand; that she is nothing more or less than the personification of all the pent up lusts, desires, ambitions and frustrations in every man's heart focused in one place. When he finally confronts her, she describes her needs in a manner worthy of a Bride of Dracula:

I want you. I want your high spots and your low spots. I want everything that's made you happy and everything that's hurt you bad. I want your first girl. I want that shiny bicycle. I want that licking. I want that pinhole camera. I want Betty's legs. I want the blue sky filled with stars. I want your mother's death. I want your blood on the cobblestones. I want Mildred's mouth. I want the first picture you sold. I want the lights of Chicago. I want gin. I want Gwen's hands. I want your wanting me. I want your life. Feed me, baby, feed me.Not a very sparkly moment nor a simple case in need of an attitude adjustment. A blood substitute would be wasted on such a succubus that Leiber has redrawn in a modern, urban setting.

In 1972, Rod Serling's Night Gallery aired their adaption of "The Girl with the Hungry Eyes". With script by Robert M Young and directed by John Badham, the teleplay was arguably superior to the short story, though it may be more of a matter of comparing a story in two different media. Besides, Leiber deserves to be offered a move and a pawn for not having Joanna Pettet around as his inspiration.

Aside from Miss Pettet, a woman who causes grown men to bite their fists and emit small animal noises, the television version fleshes out the story with some very strong dialogue, such as this speech by the beer baron Mr Munsch (John Astin) as he pleads with the photographer David Faulkner (James Farentino) to help him find the Girl so he can meet her:

There's something different about her, isn't there? It isn't sex or life or death or anything in between. Who is she? Find out. For all of our sakes, find out!The Girl is what a vampire should be; seductive, unsettling, dangerous, hungry, and unearthly in a way that suggests more than immortality on a liquid diet. She promises everything, but only delivers a glimpse into the Pit.

Thursday, 9 September 2010

Review: Midnight by the Morphy Watch

If anyone was going to write weird fiction about chess, it was going to be Fritz Leiber. Though not as well known to the general public as Robert E Howard or H P Lovecraft, Leiber was one of the defining authors of American weird fiction and a pioneer of the urban horror story that plays off the inchoate fears of the city dweller. In novels like Conjure Wife and short stories like "Smoke Ghost" and "The Girl with the Hungry Eyes" Leiber took our clean, modern world that we pride ourselves as having thrown off the superstitious and populated it with a new demonology. University campuses become the hunting grounds of witches working to advance their husbands' careers, smog and oil become tangible monsters, and photographs spawn succubi.

If anyone was going to write weird fiction about chess, it was going to be Fritz Leiber. Though not as well known to the general public as Robert E Howard or H P Lovecraft, Leiber was one of the defining authors of American weird fiction and a pioneer of the urban horror story that plays off the inchoate fears of the city dweller. In novels like Conjure Wife and short stories like "Smoke Ghost" and "The Girl with the Hungry Eyes" Leiber took our clean, modern world that we pride ourselves as having thrown off the superstitious and populated it with a new demonology. University campuses become the hunting grounds of witches working to advance their husbands' careers, smog and oil become tangible monsters, and photographs spawn succubi."Midnight by the Morphy Watch" (Worlds of If, July 1974) is a perfect example of how Leiber was able make San Francisco seem like it was on the borders of Arkham and an innocent game of chess into a gateway to Hell. The Morphy Watch is one of the Chess world's greatest lost treasures and even in real life it was the centre of an incredible story. Paul Morphy (1837-1884) was one of the great geniuses of chess. A child prodigy, he was crowned (albeit unofficially) world chess champion when only 21. Returning to his native United States, he enjoyed a hero's welcome and a celebrity life. Accolades and prizes were showered on him–one of which was a specially commissioned watch given to him by the American Watch Company that had chessmen instead of numerals on the dial. Having beaten all comers and growing increasingly eccentric, Morphy suddenly declared that chess had no more challenges for him and he retired from the game for good. Morphy later pawned the fabled watch and it passed into the hands of Arnous de Riviere. It vanished some time after 1921. It's whereabouts a mystery, Leiber provides an answer.

In "Midnight by the Morphy Watch", the titular timepiece (sorry) is rediscovered by Stirf Ritter-Rebil, an aging chess enthusiast and antiquarian, in a San Francisco secondhand shop of the sort that only do business in the pages of weird fiction. The watch is bit more elaborate than its real-life counterpart and Ritter (as he prefers to be called) soon discovers that he has purchased more than an historical curiosity. At a local chess tournament, he finds that his atrophied chess skills are returning. In fact, he is playing better than ever. Soon he is winning game after game and progresses to defeating masters while blindfolded in a simultaneous match against four opponents. As Ritter's powers grow, so does his mania for the game. He can't stop thinking about chess or dreaming about it. The game becomes literally all-consuming in Ritter's expanding mind. It also doesn't help that he is haunted by four spectral figures and a prowling "something" with a hint of the cosmic about it.

The story is a simple one with a neat twist at the end, but Leiber is able to flesh it out with his bold writing style. The characters are vivid and distinct. Ritter is fully realised and comes off the page in a way that is economical, yet effective. One suspects that there is a bit of Leiber mixed in him. Leiber's word pictures are neat little stories in themselves, such as the part where a dusty window is cleaned, without detracting from the main action. His descriptions of San Francisco linger and his blending of the earthly and the unearthly is masterful.

In all, as tidy a gem as one of Morphy's games.

Wednesday, 8 September 2010

Quote of the day

Books have the same enemies as people: fire, humidity, animals, weather, and their own content.Paul Valery

Review: The Walls of Eryx

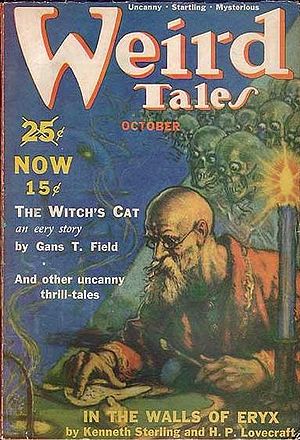

H P Lovecraft is remembered as the most influential and perhaps the greatest writer of weird fiction of the 20th century, but during his life, Lovecraft remained an impoverished writer who never had a book published and who supplemented the meager earnings from his short stories by selling his services as editor and ghost writer. Never a businessman, he didn't prosper at this either. It did, however, provide Lovecraft with an opportunity to branch out into subjects that he normally wouldn't have considered and in the 1936 Lovecraft took over a manuscript by Kenneth Sterling, which he rewrote and it was eventually published after Lovecraft's death in the October 1939 issue of Weird Tales under the tile of The Walls of Eryx. Though not the best or even the more adequate of Lovecraft's collaborations, it is notable as his single foray into interplanetary adventure fiction.

H P Lovecraft is remembered as the most influential and perhaps the greatest writer of weird fiction of the 20th century, but during his life, Lovecraft remained an impoverished writer who never had a book published and who supplemented the meager earnings from his short stories by selling his services as editor and ghost writer. Never a businessman, he didn't prosper at this either. It did, however, provide Lovecraft with an opportunity to branch out into subjects that he normally wouldn't have considered and in the 1936 Lovecraft took over a manuscript by Kenneth Sterling, which he rewrote and it was eventually published after Lovecraft's death in the October 1939 issue of Weird Tales under the tile of The Walls of Eryx. Though not the best or even the more adequate of Lovecraft's collaborations, it is notable as his single foray into interplanetary adventure fiction.The Walls of Eryx tells of the fate of Kenton Stanfield, a prospector from Earth who is hired by a mining company to hunt for Venusian crystals that are sources of tremendous energy. Unfortunately, they are also worshiped by the primitive reptilian natives, who do not take kindly to the Earthmen's gathering them and are a constant hazard. So far, it sounds a bit like the plot of Avatar, but the natives are scarcely Cameron's noble savages and Stanfield soon learns that the natives have a sadistic streak wide enough to land an A380 on.

Lovecraft/Sterling's Venus is, in keeping with the science of the 1930s, a hot, humid jungle world teeming with all manner of life and, this being Lovecraft, none of it is scenic or beautiful and all of it is unpleasantly deadly. Stanton can only survive in the poisonous atmosphere with a chemically-charged oxygen mask and he is clad head to toe in a leather suit to protect him from the local nasties. Prospectors of the future apparently travel very light because outside of some food tablets, a knife, a "flame gun" and a crystal detector, Stanton seems rather under-equipped for a jungle expedition.

Stanton's seemingly routine outing (if ambushes and an encounter with a hallucinatory cannibal plant can be called routine) takes on a bizarre twist when he comes across an unusually large crystal clutched in the dead hand of an expired fellow prospector lying in a clearing. If this wasn't odd enough, the corpse turns out to be lying at the entrance of a 100-yard wide invisible building that fills the entire clearing. Collecting his prize, Stanton decides to explore the unseen interior of the structure, but when he attempts a few minutes later to leave its empty, twisting corridors, he discovers to his horror that the building is, in fact, a maze. Unless he can find some means of escape, Stanton faces a slow death by starvation, thirst, and suffocation–a fact that he is constantly reminded of as the body of the other Earthman starts to rot and decay in the Venusian environment. If that isn't bad enough, the natives, whom Stanton learns built the maze, gather to amuse themselves by standing at the edge of clearing to watch him die.

The Walls of Eryx is clearly a steal from Stanley G. Weinbaum's Parasite Planet that was published in Astounding Stories in February of 1935. Lovecraft/Sterling's Venus is so similar to Weinbaum's that it feels like a motion picture filmed on a set built for another production. The main character being a lone prospector tramping through the jungle with a flame pistol and canteen is too close to Weinbaum's "Ham" Hamilton to be coincidence. The trouble is, that while Lovecraft/Sterling lifted the background, they left behind the sense of place and air of adventure. They also forgot the humour, but we're talking about Lovecraft here; a man who was not exactly the P G Wodehouse of his generation.

The story also suffers because after a promising set up neither Lovecraft nor Sterling can figure out what to do with Stanton once he gets trapped in the maze. A death by slow starvation and thirst doesn't have much dramatic promise unless the character can provide some sort of revelation or emotions that make us suffer with him. For all his frustration and fear, Stanton is altogether too clinical and detached and the authors don't give his situation enough of a sense of suspense or urgency. There isn't much to Stanton and he doesn't have any inner life, so we really don't care much for him or his plight.

On the other hand, Lovecraft does manage to give The Walls of Eryx that touch of the otherworldly that sparks the imagination and raises the hairs on the back of the neck. By implying that there is far more to the natives than meets the eye, that there are more powerful and terrifying forces at work, and that the Earthmen ignore this at their peril, he gives the story a depth that sets it apart from its pulp origins.

Tuesday, 7 September 2010

The Booker Prize short list

The short list of contenders for the Booker Prize has been announced.

As usual, it's half a dozen authors that I've never heard of for books that have a combined readership smaller than that of Cooking Kosher with Adolf Eichmann.

As usual, it's half a dozen authors that I've never heard of for books that have a combined readership smaller than that of Cooking Kosher with Adolf Eichmann.

Monday, 6 September 2010

Sunday, 5 September 2010

Mark Twain and the Law of the Raft

Frederik Pohl looks at the writings of Mark Twain.

Quote of the day

Eccentricity is not, as dull people would have us believe, a form of madness. It is often a kind of innocent pride, and the man of genius and the aristocrat are frequently regarded as eccentrics because genius and aristocrat are entirely unafraid of and uninfluenced by the opinions and vagaries of the crowd.Edith Sitwell

Thursday, 2 September 2010

Quote of the day

Some circumstantial evidence is very strong, as when you find a trout in the milk.

Henry David Thoreau

Wednesday, 1 September 2010

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)