Saturday 30 April 2011

Friday 29 April 2011

Thursday 28 April 2011

Wednesday 27 April 2011

Tuesday 26 April 2011

Review: Dark Lover

Dark Lover by J R Ward (2005)

My choice of what fiction I read revolves around a number of reasons. Sometimes I read a book because I'm doing research for my site Tales of Future Past. Sometimes it's because the work is topical. And (rarely) I might even read one for pleasure. Then there are the times when I read something because the wife asks me to. She does this because she knows that my opinions of books are completely honest and she's willing to put up with my tendency to disembowel a work if I feel it deserves it.

Such is the reason why I read Dark Lover.

Let the disemboweling begin.

You can't judge a book by its cover, but you can judge it by the author's photo. If the writer is awkwardly posed, looking distinctly embarrassed or uncomfortable, is slightly blurry because he refused to sit still, or has the air of someone who is dead tired because the photographer needed twelve hours to get a decent head shot, then I conclude that this is a book worth at least skimming. On the other hand, if the author is enjoying herself, strikes a self-conscious pose or, worse, affects some sort of costume, then I know that I'm in for dreck. If said photo is appended to a doorstop novel that is the first in a twelve volume series, then I know that it will be a pile of steaming, freshly regurgitated dreck with a side order of tedium.

Such is Dark Lover. I haven't any liking for the subgenre known as "paranormal romance". Frankly, I regard the entire field as twee and more than a little embarrassing even in the abstract. Sort of like Mills & Boon with fangs. But then, fangs ain't what they used to be. I prefer my vampires out of Bram Stoker, not Barbara Cartland. However, I was willing to set aside my dislike for the genre and judge Dark Lover as I would a bit of general fantasy fiction. Then I read the pile of... but I don't use that sort of language in a review. Let's give the paperback edition's blurb writer the honour of providing the synopsis:

And it gets worse. Vampire Warriors. "Vampire" is already a red flag in modern fiction. Any work that uses the word "warrior" when not referring to real soldiers is as bad. The two in tandem is critical mass of badness. Ward compounds this by giving her "warriors" names like Rhage, Dhestroyer, Vishous, Phury, Rehvenge and Tohrment. Apparently the vampire educational system leaves much to be desired when it comes to spelling. They are all completely interchangeable versions of Ward's ideal lover–which is apparently a giant, greasy biker in leathers who spouts street slang. The biker, not the leathers.

Writing this amateurish usually doesn't make it to the book stalls without an armed escort. Ward's style is painfully cinematic to the point where she comes across as a bodice-ripping J K Rowling. This is not a good thing. She also seems to be writing for a market with the IQ of a pair of dice, since she feels obligated to provide a glossary for people who can't remember what the word "vampire" means. We're lucky she doesn't mark each page with an arrow marked "this end up". Then there's her inability to grasp the concept of showing instead of telling. Her idea of characterisation is to tell you what this or that person is like. Tell as in flat exposition. Show an event unfold? Nope. Just give us a synopsis after the fact. And never, ever, let a character do something for themselves. Repeat as necessary. It's like bad opera without the music.

Dark Lover is a book that I can honestly say that I couldn't put down. I didn't dare to because if I did, I'd start pounding it with a mallet; unable to stop until I was sobbing and retching.

My choice of what fiction I read revolves around a number of reasons. Sometimes I read a book because I'm doing research for my site Tales of Future Past. Sometimes it's because the work is topical. And (rarely) I might even read one for pleasure. Then there are the times when I read something because the wife asks me to. She does this because she knows that my opinions of books are completely honest and she's willing to put up with my tendency to disembowel a work if I feel it deserves it.

Such is the reason why I read Dark Lover.

Let the disemboweling begin.

|

| Warning label. |

Such is Dark Lover. I haven't any liking for the subgenre known as "paranormal romance". Frankly, I regard the entire field as twee and more than a little embarrassing even in the abstract. Sort of like Mills & Boon with fangs. But then, fangs ain't what they used to be. I prefer my vampires out of Bram Stoker, not Barbara Cartland. However, I was willing to set aside my dislike for the genre and judge Dark Lover as I would a bit of general fantasy fiction. Then I read the pile of... but I don't use that sort of language in a review. Let's give the paperback edition's blurb writer the honour of providing the synopsis:

In the shadows of the night in Caldwell, New York, there's a deadly turf war going on between vampires and their slayers. There exists a secret band of brothers like no other—six vampire warriors, defenders of their race. Yet none of them relishes killing their enemies, the lessers, more than Wrath, the leader of the Black Dagger Brotherhood....Four full stops in the ellipsis. Oh, dear. As a piece of sales copy, it's not bad. Not when you consider that it shields the potential reader from the awfulness of the novel like a yard of lead. This is the sort of book that has lines like:

The only purebred vampire left on the planet, Wrath has a score to settle with the slayers who murdered his parents centuries ago. But, when one of his most trusted fighters is killed—orphaning a half-breed daughter unaware of her heritage or her fate—Wrath must usher the beautiful female into the world of the undead....

Racked by a restlessness in her body that wasn't there before, Beth Randall is helpless against the dangerously sexy man who comes to her at night with shadows in his eyes. His tales of brotherhood and blood frighten her. But his touch ignites a dawning hunger that threatens to consume them both....

Her core bloomed for him.I laughed so hard when I read it that I had to wipe the tears off my glasses. This is truly bad. Dark Lover isn't so much a novel as a roll call of clichés. Beautiful heroine whom everyone falls over like the lead character in Mary Sue fanfiction? Check. Lecherous boss so broadly stereotyped that he reads as if written in with crayon? Check. Tough-as-nails homicide detective who shows the perps how they do things downtown? Check. Hero with volcanic passions and a turbulent past only because the author says so? Check. Frat boy rapist straight out of that Duke University travesty? Check. Hero that makes Fabio in his prime look like Don Knotts? Check. Ludicrous underground vampire society? Check. Vampires who aren't really vampires? Check. Secret war between shadow armies? Check. Really, really bad sex scenes. Oh, boy, Check. Voldemort knock-off villain? Check. Plot so predictable that you can write the blurb before even turning the book over? Check and double check. There's even a character called "Mr X" for pity's sake! Check!

And it gets worse. Vampire Warriors. "Vampire" is already a red flag in modern fiction. Any work that uses the word "warrior" when not referring to real soldiers is as bad. The two in tandem is critical mass of badness. Ward compounds this by giving her "warriors" names like Rhage, Dhestroyer, Vishous, Phury, Rehvenge and Tohrment. Apparently the vampire educational system leaves much to be desired when it comes to spelling. They are all completely interchangeable versions of Ward's ideal lover–which is apparently a giant, greasy biker in leathers who spouts street slang. The biker, not the leathers.

Writing this amateurish usually doesn't make it to the book stalls without an armed escort. Ward's style is painfully cinematic to the point where she comes across as a bodice-ripping J K Rowling. This is not a good thing. She also seems to be writing for a market with the IQ of a pair of dice, since she feels obligated to provide a glossary for people who can't remember what the word "vampire" means. We're lucky she doesn't mark each page with an arrow marked "this end up". Then there's her inability to grasp the concept of showing instead of telling. Her idea of characterisation is to tell you what this or that person is like. Tell as in flat exposition. Show an event unfold? Nope. Just give us a synopsis after the fact. And never, ever, let a character do something for themselves. Repeat as necessary. It's like bad opera without the music.

Dark Lover is a book that I can honestly say that I couldn't put down. I didn't dare to because if I did, I'd start pounding it with a mallet; unable to stop until I was sobbing and retching.

Monday 25 April 2011

Review: Little Lost Robot

"Little Lost Robot" by Isaac Asimov (1947)

Careless talk costs lives. It also lead to some knotty problems when there's a literal-minded robot within earshot. At Hyper Base, a secret government space station dedicated to developing faster than light travel, an aggravated scientist loses his patience with a robot and tells it to get lost–and it promptly does so by hiding among an arriving shipment of identical robots. This would be merely annoying, except that this robot is a special job with a modified version of the First Law: It can't harm a human being, but it can allow a human being to come to harm. This makes it an extremely dangerous piece of machinery that must be located or the alternative is destroying over five dozen extremely valuable robots. So, the Solar System's leading robopsychologist, Dr Susan Calvin is brought in to try to find some way of finding the little lost robot who does not wish to be found.

Isaac Asimov's robot stories had a great impact on the development of science fiction by introducing the idea that robots, like all other machines, would be built with safeguards. They also went a long way toward making robots sympathetic characters and it was through stories like "Little Lost Robot" that the line runs to Robby the Robot, C3PO, and R2D2. That being said, this story, like the rest of Asimov's robot series, aren't so much stories as logic problems disguised as fiction. Indeed, they often read like padded out Minute Mysteries and I'm often expecting to be directed to turn the page upside down to read the answer. Structurally, they are also like rather pedestrian whodunnits with the crime, the dilemma, the detective, the red herrings, and the solution tied up in a neat bow at the end. That's all very well if one is approaching such a story like working a crossword puzzle (which many mysteries freely admit to being akin to), but as a work of drama, the robot series are singularly unsatisfying.

One problem, as with all of Asimov's writing, is his utter inability to master description. Reading an Asimov story, it is impossible to hold any sort of picture in one's mind as to where the story is taking place, or what anything is. These are stories about robots, for example, yet it is impossible from reading Asimov to come away with any sense of what sort of machines they are except that they are metallic. Are they roughly humanoid machines? Do they look like suits of armour? Metal mannequins? Are they clumsy? Graceful? Awe-inspiring? Crude? What? I don't expect a detailed catalogue, but at least throw in the odd simile. We aren't even told what the robots on Hyper Base are for. What work do they do? Why are they indispensable? There are human labourers there, so why the robots? Is it just to provide grist for a mystery story?

The same goes for characters. Asimov was very fond of his creation Susan Calvin, but she is little more than a sustained waspish attitude latched to a Miss Marple knock off. The other characters in the story are wildly inconsistent, vacillating between belligerence and deference in a heartbeat. Motivations are never very strong, conflict comes across as something that Asimov would rather not deal with if he has a choice, and, as usual, the author hangs much of the story on contrived psychological "facts" that have no basis in the real world. Worse, the dilemma can only be sustained by praying that the reader keeps overlooking one question: Why aren't the robots isolated from one another so that the one being sought can't cheat against the tests to find it?

"Little Lost Robot" isn't a bad story. In fact, it could be salvaged very easily if it was placed in the hands of another writer who actually has some affinity with human beings rather than sci fi concepts. This isn't even conjecture. In the 1960s, the television series Out of This World adapted the story for the talking fish tank. Read the original and compare it to the television version and one sees the difference. In the later, Dr Calvin comes across as a three dimensional character with motivation and courage who actually likes talking to other people and can even be charming. The base commander grows roses, the lost robot is cunning and even a bit sinister, and the engineer Black, who in the story is a passing moment of beefy bluster, is the real villain of the piece and a source of solid conflict. Finally, the ending in the print version is basically "Well, we've caught the robot. Bye". But on the screen it ends on a disturbing note as the lost robot murders Black and it's pointed out to us that the other robots, which are being shipped to the four corners of the system, have witnessed it and know that such a thing is possible. What will they make of that precedent?

First Law:

A robot may not injure a human being, or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

Second Law:

A robot must obey orders given it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

Third Law:

A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Careless talk costs lives. It also lead to some knotty problems when there's a literal-minded robot within earshot. At Hyper Base, a secret government space station dedicated to developing faster than light travel, an aggravated scientist loses his patience with a robot and tells it to get lost–and it promptly does so by hiding among an arriving shipment of identical robots. This would be merely annoying, except that this robot is a special job with a modified version of the First Law: It can't harm a human being, but it can allow a human being to come to harm. This makes it an extremely dangerous piece of machinery that must be located or the alternative is destroying over five dozen extremely valuable robots. So, the Solar System's leading robopsychologist, Dr Susan Calvin is brought in to try to find some way of finding the little lost robot who does not wish to be found.

Isaac Asimov's robot stories had a great impact on the development of science fiction by introducing the idea that robots, like all other machines, would be built with safeguards. They also went a long way toward making robots sympathetic characters and it was through stories like "Little Lost Robot" that the line runs to Robby the Robot, C3PO, and R2D2. That being said, this story, like the rest of Asimov's robot series, aren't so much stories as logic problems disguised as fiction. Indeed, they often read like padded out Minute Mysteries and I'm often expecting to be directed to turn the page upside down to read the answer. Structurally, they are also like rather pedestrian whodunnits with the crime, the dilemma, the detective, the red herrings, and the solution tied up in a neat bow at the end. That's all very well if one is approaching such a story like working a crossword puzzle (which many mysteries freely admit to being akin to), but as a work of drama, the robot series are singularly unsatisfying.

One problem, as with all of Asimov's writing, is his utter inability to master description. Reading an Asimov story, it is impossible to hold any sort of picture in one's mind as to where the story is taking place, or what anything is. These are stories about robots, for example, yet it is impossible from reading Asimov to come away with any sense of what sort of machines they are except that they are metallic. Are they roughly humanoid machines? Do they look like suits of armour? Metal mannequins? Are they clumsy? Graceful? Awe-inspiring? Crude? What? I don't expect a detailed catalogue, but at least throw in the odd simile. We aren't even told what the robots on Hyper Base are for. What work do they do? Why are they indispensable? There are human labourers there, so why the robots? Is it just to provide grist for a mystery story?

The same goes for characters. Asimov was very fond of his creation Susan Calvin, but she is little more than a sustained waspish attitude latched to a Miss Marple knock off. The other characters in the story are wildly inconsistent, vacillating between belligerence and deference in a heartbeat. Motivations are never very strong, conflict comes across as something that Asimov would rather not deal with if he has a choice, and, as usual, the author hangs much of the story on contrived psychological "facts" that have no basis in the real world. Worse, the dilemma can only be sustained by praying that the reader keeps overlooking one question: Why aren't the robots isolated from one another so that the one being sought can't cheat against the tests to find it?

"Little Lost Robot" isn't a bad story. In fact, it could be salvaged very easily if it was placed in the hands of another writer who actually has some affinity with human beings rather than sci fi concepts. This isn't even conjecture. In the 1960s, the television series Out of This World adapted the story for the talking fish tank. Read the original and compare it to the television version and one sees the difference. In the later, Dr Calvin comes across as a three dimensional character with motivation and courage who actually likes talking to other people and can even be charming. The base commander grows roses, the lost robot is cunning and even a bit sinister, and the engineer Black, who in the story is a passing moment of beefy bluster, is the real villain of the piece and a source of solid conflict. Finally, the ending in the print version is basically "Well, we've caught the robot. Bye". But on the screen it ends on a disturbing note as the lost robot murders Black and it's pointed out to us that the other robots, which are being shipped to the four corners of the system, have witnessed it and know that such a thing is possible. What will they make of that precedent?

Sunday 24 April 2011

Saturday 23 April 2011

Friday 22 April 2011

Quote of the day

A schedule broken at will becomes a mere procession of vagaries.

Rex Stout

We hope you've enjoyed Quote of the Day. This feature is being discontinued and will now appear only occasionally.

Review: Black Mischief

Black Mischief by Evelyn Waugh (1932)

Seth, Emperor of Azania, Chief of the Sakuyu, Lord of Wanda, Tyrant of the Seas, and Bachelor of the Arts of Oxford University is determined to be the apostle of Progress and the Future for his country. Unfortunately, his vision of the Future is based upon whatever he happens to be reading at the moment. This is never good and it is particularly bad in an African autocrat of an state so backward that cannibalism is still pretty high on the local menu.

Actually, Waugh's Azania is a parody of a fairly accurate description of every failed African state up to the time of publication. It's a miserable cross section of native tribalism, Arab slave trading, and half-hearted European contact that has resulted in a savage back country ruled by a fly-specked capital city loaded with Imperial flotsam and jetsam. The vainglorious Seth is determined to haul Azania into the 20th century, but he has no idea what he's doing, how money works, or the fact that he's barely holding on to power by his finger nails after a civil war with his uncle that had half the capital's population running for the boats. Into this comes Seth's old university classmate Basil Seal, a British reprobate of the first water, who becomes his Minister for Modernisation. Added is a dipsomaniac Irish ex-pat head of the army, the British legation who are more interested in the latest mail from London than anything happening around them, and the French ambassador who is convinced that his British counterpart is a Machiavellian genius. In a land where people still sharpen their teeth, this is a bad combination.

Black Mischief is Waugh's third novel and it has a bite that never lets up. Seth is a wonderfully comic figure who is hopelessly lost in his vision of himself and utterly unable to understand the country he rules and wants to fundamentally change Small wonder that he sounds rather like a particular 21st century American president. Azania itself is like an untamed force of nature filled with deep-running native currents that make Seth's modernisation efforts seem like pounding sand–especially when they are in the hands of a man like Basil, who only came out to Azania because he found London too much of a bore.

Waugh's gimlet-eyed satire is relentless from his portrayal of the oblivious British legation to the conspiracy-obsessed French to the opportunistic Armenian merchant. No one is spared as along the way we are treated to a pair of clueless animal rights activists whom the native nobility think are actually promoting cruelty to animals, an English girl who thinks that life can be reduced to necking and bad novel writing, and a bewildered 90-year old pretender to the throne who's spent most of his life chained in a cave. All of this climaxes in a farcical carnival of contraception (don't ask) that descends into chaos and coup in short order as Waugh's dramatic curve alternates between farce and horror.

Mischievous and dark fun all around.

Seth, Emperor of Azania, Chief of the Sakuyu, Lord of Wanda, Tyrant of the Seas, and Bachelor of the Arts of Oxford University is determined to be the apostle of Progress and the Future for his country. Unfortunately, his vision of the Future is based upon whatever he happens to be reading at the moment. This is never good and it is particularly bad in an African autocrat of an state so backward that cannibalism is still pretty high on the local menu.

Actually, Waugh's Azania is a parody of a fairly accurate description of every failed African state up to the time of publication. It's a miserable cross section of native tribalism, Arab slave trading, and half-hearted European contact that has resulted in a savage back country ruled by a fly-specked capital city loaded with Imperial flotsam and jetsam. The vainglorious Seth is determined to haul Azania into the 20th century, but he has no idea what he's doing, how money works, or the fact that he's barely holding on to power by his finger nails after a civil war with his uncle that had half the capital's population running for the boats. Into this comes Seth's old university classmate Basil Seal, a British reprobate of the first water, who becomes his Minister for Modernisation. Added is a dipsomaniac Irish ex-pat head of the army, the British legation who are more interested in the latest mail from London than anything happening around them, and the French ambassador who is convinced that his British counterpart is a Machiavellian genius. In a land where people still sharpen their teeth, this is a bad combination.

Black Mischief is Waugh's third novel and it has a bite that never lets up. Seth is a wonderfully comic figure who is hopelessly lost in his vision of himself and utterly unable to understand the country he rules and wants to fundamentally change Small wonder that he sounds rather like a particular 21st century American president. Azania itself is like an untamed force of nature filled with deep-running native currents that make Seth's modernisation efforts seem like pounding sand–especially when they are in the hands of a man like Basil, who only came out to Azania because he found London too much of a bore.

Waugh's gimlet-eyed satire is relentless from his portrayal of the oblivious British legation to the conspiracy-obsessed French to the opportunistic Armenian merchant. No one is spared as along the way we are treated to a pair of clueless animal rights activists whom the native nobility think are actually promoting cruelty to animals, an English girl who thinks that life can be reduced to necking and bad novel writing, and a bewildered 90-year old pretender to the throne who's spent most of his life chained in a cave. All of this climaxes in a farcical carnival of contraception (don't ask) that descends into chaos and coup in short order as Waugh's dramatic curve alternates between farce and horror.

Mischievous and dark fun all around.

Thursday 21 April 2011

Quote of the day

It is a capital mistake to theorize before you have all the evidence. It biases the judgment.

Sherlock Holmes

Yes, I know he'd fictional, but I can scarcely credit his editor Conan Doyle, can I?

Wednesday 20 April 2011

Quote of the day

Write me a creature that thinks as well as a man or better than a man, but not like a man.

John W. Campbell Jr.

Review: Who Goes There?

"Who Goes There?" by Don A Stuart (AKA John W Campbell Jr.) (1938)

In the 1930s, the Second Magnetic Expedition to Antarctica finds more than it bargains for. Investigating a magnetic anomaly some 80 miles from base at the South Magnetic Pole, the scientists discover the wreck of a spacecraft that crashed and was embedded in the ice over 20 million years ago. Trying to remove the craft from the ice, the thermite charges they use accidentally destroy it, but they manage to recover the frozen body of one of the occupants, who was thrown clear. Returning to base, they debate whether or not to thaw out their find for study, but there's resistance–partly due to fear of alien germs, but mainly because the three-eyed horror in the ice looks like a refugee from the Pit. But thaw it they do, only to discover that even after 20 million years the thing is alive and it is a man-eating shape shifter with the power to perfectly mimic the form and behaviour of any living thing it devours. The 37 men of the expedition are faced with the nightmare of not knowing who is human and who is an invader bent on taking over the world in the most complete manner possible–not by ruling it, but by replacing all life with itself.

"Who Goes There?" is remembered today mostly for being the basis for the 1951 film The Thing From Another World and the 1982 remake The Thing–which is a pity because Campbell's novella stands perfectly well on its own feet. It can even be argued that as a horror story it still does a better job than either of its cinematic incarnations. Campbell introduces a truly original mystery: How do you uncover a monster in your midst who can copy a man right down to his cells and his very thoughts? What sort of a test can you devise? And how do you do it before the thing manages to devour and replace everyone else? On it's own, this would be a wonderful little detective story that keeps the reader second guessing how our heroes will solve their problem, but Campbell ups the stakes a notch.

Taking obvious inspiration from H P Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness, he lifts a simple bit of science fiction and turns it into a truly unsettling horror tale. Early in the story, the scientists seemingly destroy the original thing when they find it trying to absorb one of their sled dogs, but their relief is very short lived when they realise that they've no reason to assume that the man they left to guard the thawing thing is still human. Worse, they have no reason to assume that any of them are, so a large part of the plot is taken up by the expedition members living under increasing fear and anxiety as they hunt for a solution. Isolating themselves from the outside world by destroying their aeroplane and tractors, the men live an existence of constantly watching one another while every man worries whether or not he might be the only human left. Campbell never allows the pressure to let up as tests become blind alleys and it becomes clear that time is running out.

It's not a perfect story. Though the characters are very well delineated for a pulp story, it's obvious from the first page who Our Hero is and it's highly improbable that he'll turn into alien chowder. On the other hand, we do feel for the deaths of other characters. Campbell also gets points for doing his homework on Antarctic exploration and he provides a real feel for the sights, sounds, and smells of men living in such a confined world. Finally, he provides a nice little kicker at the end that reminds us that this is, in fact sci fi and not a horror outing.

In all, a satisfying read, but I'd recommend that you do so on a summer afternoon and not on a blizzardy winter's evening.

Tuesday 19 April 2011

Quote of the day

I have memories–but only a fool stores his past in the future.

David Gerrold

Review: Star Trek: U.S.S. Enterprise Haynes Manual

Star Trek: U.S.S. Enterprise Haynes Manual by Ben Robinson and Marcus Riley

Science fiction fans are a bit like Horatio Hornblower fans; the fiction is no fun unless you can wallow in the technical details as well. Back in the 1970s, the first attempt to give fans a behind the scene look at "treknology" was the Star Trek: Star Fleet Technical Manual, which purported to give the reader all the background on warp drive, how phasers worked, and even sewing patterns for "official" uniforms. It was a paperback in a plastic slip cover and had a crude, mechanical draughting feel to it, but that helped to give it an air of authenticity. Since then, we've had Star Trek blueprints, medical manuals, and heaven knows what else.

The latest variation on this gag is the Star Trek: U.S.S. Enterprise Haynes Manual. It tries to be an update on the earlier version and strives to give a bigger boost through more sophisticated graphics, but in the end it is a perfect example of how less is more. The cutaway diagrams are fun and some bits of trivia such as how the navigation console of the original series evolved is interesting for those with an eye for set design, but the attempt to cover all the series and films while including expositions of fanciful pseudoscience and potted non-history is ultimately tedious. Forty years ago, such a book would have been a nerd's dream by allowing him to relive old television adventures in his head, but since the invention of video, these sort of books are only for the diehard trekkie.

Science fiction fans are a bit like Horatio Hornblower fans; the fiction is no fun unless you can wallow in the technical details as well. Back in the 1970s, the first attempt to give fans a behind the scene look at "treknology" was the Star Trek: Star Fleet Technical Manual, which purported to give the reader all the background on warp drive, how phasers worked, and even sewing patterns for "official" uniforms. It was a paperback in a plastic slip cover and had a crude, mechanical draughting feel to it, but that helped to give it an air of authenticity. Since then, we've had Star Trek blueprints, medical manuals, and heaven knows what else.

The latest variation on this gag is the Star Trek: U.S.S. Enterprise Haynes Manual. It tries to be an update on the earlier version and strives to give a bigger boost through more sophisticated graphics, but in the end it is a perfect example of how less is more. The cutaway diagrams are fun and some bits of trivia such as how the navigation console of the original series evolved is interesting for those with an eye for set design, but the attempt to cover all the series and films while including expositions of fanciful pseudoscience and potted non-history is ultimately tedious. Forty years ago, such a book would have been a nerd's dream by allowing him to relive old television adventures in his head, but since the invention of video, these sort of books are only for the diehard trekkie.

Monday 18 April 2011

Quote of the day

A ruffled mind makes a restless pillow.

Charlotte Bronte

Sunday 17 April 2011

Saturday 16 April 2011

Friday 15 April 2011

Quote of the day

It is impossible to imagine Goethe or Beethoven being good at billiards or golf.

H. L. Mencken

Thursday 14 April 2011

Quote of the day

Individual science fiction stories may seem as trivial as ever to the blinder critics and philosophers of today - but the core of science fiction, its essence has become crucial to our salvation if we are to be saved at all.

Isaac Asimov

Review: The Last Question

"The Last Question" by Isaac Asimov (1956)

"The Last Question" by Isaac Asimov (1956)In the 21st century,computers are a fact of life. Once exotic machines that few people saw and fewer understood, computers are not found everywhere. Home, office, supermarket, or coffee shop; no matter where you go, you're likely to find one. Even if you travel half a world and try to hide in the rudest African hut, odds are that the local Masai hunter will have a cell phone tucked into his garments–a phone that includes a computer more powerful than any on Earth during the 1960s.

Today, computers are so common that they've gone from discrete machine to components in other devices. But in 1956 when Isaac Asimov published "The Last Question", it was a very different world. Then, there were only a handful of computers on the entire planet. They were gigantic things that were so large that they were often incorporated into the very architecture of the buildings that contained them. Unlike today when a four-year old can operate a computer so well that you have to make sure to keep ebay on the blocked sites list, the computers of the 1950s used only arcane machine languages that were as hard to decipher as the pronouncements of an oracle. And they were so expensive that even the experts in computer science had very little hands-on experience in trying to figure out what they could really do or what their limitations were.

Its small wonder, therefore, that the 1950s saw the birth of Asimov's Multivac series. The name "Multivac" was a play on the sort of exotic monikers that computers sported in those days. Eniac, Univac, Multivac; its was a natural progression. Multivac, according to Asimov in "The Last Question", was the ultimate in computers; a 21st century computer covering many cubic miles and so complex that the men who built and maintained it have only

(A) vague notion of the general plan of relays and circuits that had long since grown past the point where any single human could possibly have a firm grasp of the whole.As for the technicians,

Multivac was self-adjusting and self-correcting. It had to be, for nothing human could adjust and correct it quickly enough or even adequately enough. So (they) attended the monstrous giant only lightly and superficially, yet as well as any men could. They fed it data, adjusted questions to its needs and translated the answers that were issued. Certainly they, and all others like them, were fully entitled to share in the glory that was Multivac's.In other words, Multivac is a secular version of God; made in man's image, powerful, beneficent, and (above all) tame. In another writer, this paragraph would be called foreshadowing, but Asimov never indulged in anything so subtle. This is merely tipping his hand.

Once he's set up Multivac for the reader, Asimov moves to the meat of the short story. Multivac, apparently all on his lonesome, has perfected solar power and provided mankind with a limitless source of power. Two technicians, getting drunk in celebration, argue about whether or not that means power "forever" with one technician arguing that because of entropy there can't be a "forever" because all the stars in the universe will eventually run down even if it takes tens of trillions of years. This being the 1950s, I should have been surprised that Asimov doesn't bother to at least give the Steady State theory a look in, but why becomes obvious later.

"The Last Question" is very simple in structure. It's a series of very simple vignettes where a couple characters hundreds, millions, or billions of years in the future retread the argument of the two technicians and, like the two, asks the same question,

How can the net amount of entropy of the universe be massively decreased?Multivac always answers,

THERE IS AS YET INSUFFICIENT DATA FOR A MEANINGFUL ANSWER.Multivac always talks in All Caps. As the same question is asked we see each new version of Multivac grow from giant building to taking up whole planets to residing somewhere in hyperspace. Eventually, Multivac sounds so much like Deep Thought I kept expecting a couple of irate philosophers to barge in. Meanwhile, mankind expands exponentially until it occupies every planet in every galaxy in the universe. All very Malthusian, but then, population dynamics were never Asimov's strong suit.

The interesting thing about "The Last Question" is that it shows the nature of Asimov's interest in the human race. He didn't have one. Whether short story or novel, for Asimov humanity was just masses that acted as a backdrop for his ideas. In this story, we get a potted history of man from now until doomsday, yet there is no sense of progress, setback, struggle, or ambition as a Wells or a Stapledon would have offered. Nor is there any sense of common joys and sorrows that every person experiences. The closest Asimov comes to this is with the introduction of a family emigrating to the stars–and the twin girls are nothing more than shrieking irritants. In all, existence according to Asimov is pretty pointless. He can't even care enough about humanity to offer up a sense of tragedy. Instead, as the heat death of the universe looms, mankind merges with the AC (the ulitmate version of Multivac),

One by one Man fused with AC, each physical body losing its mental identity in a manner that was somehow not a loss but a gain.Yes, we get the usual sci fi dream of those days of a future ending in the death of the individual and a life of pure thought. At any rate, the last of Man asks the question again and then asks if there is a solution. Regrettably, the computer doesn't start talking about building a new computer whose merest parameters it is not worthy to compute, but pronounces,

NO PROBLEM IS INSOLUBLE IN ALL CONCEIVABLE CIRCUMSTANCES.

For the ultimate computer, Multivac clearly has some fundamental gaps in its databanks.

One thing that Asimov is good at is grasping that a short story is essentially a "gag" and that everything boils down to the punchline. In this case, Multivac is left the sole entity in the entire universe (Why it survives is glossed over unconvincingly) until it finds the solution at last and proclaims,

LET THERE BE LIGHT!It's a nice ending, but Fredric Brown got there a lot quicker and with more impact.

Wednesday 13 April 2011

Quote of the day

If you have a garden and a library, you have everything you need.

Cicero

Tuesday 12 April 2011

Quote of the day

It is very comforting to believe that leaders who do terrible things are, in fact, mad. That way, all we have to do is make sure we don't put psychotics in high places and we've got the problem solved.

Tom Wolfe

Monday 11 April 2011

Quote of the day

A skittish motorbike with a touch of blood in it is better than all the riding animals on earth, because of its logical extension of our faculties, and the hint, the provocation, to excess conferred by its honeyed untiring smoothness.

T E Lawrence

Sunday 10 April 2011

Saturday 9 April 2011

Friday 8 April 2011

Quote of the day

I think to be oversensitive about cliches is like being oversensitive about table manners.

Evelyn Waugh

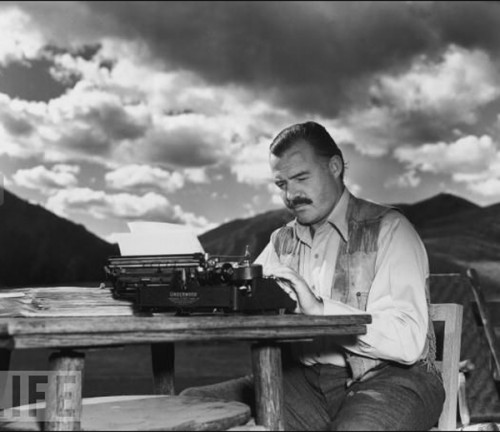

Typewriters

Flavorwire looks at Famous authors and their typewriters.

Actually, it's more authors, celebrities, and their typewriters, but it is kind of nice to see people sitting down at the machine that says "writer" so much more clearly than a computer ever could.

Actually, it's more authors, celebrities, and their typewriters, but it is kind of nice to see people sitting down at the machine that says "writer" so much more clearly than a computer ever could.

Thursday 7 April 2011

Quote of the day

This is horror, admitted, of a sort, but it is horror perpetrated by unhuman beings. They're not relatable to Dad–at least, I hope they're not! And it's entirely harmless in this context. (On his creation, the Cybermen, in Doctor Who)

Kit Pedler

Review: Mutant 59: The Plastic Eaters

Mutant 59: The Plastic Eaters by Kit Pedler and Gerry Davis (1972)

We live in a plastic world. Take a moment to look around you and note how many things are made of or include plastic components. Go on. I'll wait.

A pretty large number, isn't it? From my desk where I type on a plastic keyboard in front of a plastic monitor connected to a computer by plastic-coated wires to a computer made up of plastic bits and pieces I can see plastic bottles, a plastic lamp, plastic telephones, a plastic camping lantern, plastic boxes, plastic wrappers, plastic carpeting, plastic paint on the wall, plastic laminate on the desk, plastic soles on my shoes, plastic picture frames with plastic "glass", my clothing is partly plastic and even some the furniture is held together with plastic bits. And that's just what I can see at a glance. There's plastic everywhere. Step into a commercial airliner and the passenger cabin is a plastic tube with plastic fittings. Some planes are made entirely of plastic; as are boats, cars, and... the list goes on and on.

In fact, it's scary. Why scary? Because we are utterly dependent on plastics. It's replaces a phenomenal number of materials and many things we take for granted today couldn't be made out of anything else except plastic. That's true today and it was true back in 1972 when plastics had only been in truly common use for about ten years. That was when the writing team of Kit Pedler and Gerry Davis asked the question: What would happen if all that plastic suddenly went away. And thus was born Mutant 59: The Plastic Eaters.

The premise of Mutant 59 is simple. Owing to an improbable chain of events, a bacteria is created that is able to feed off plastic. At first, it's only a few types, but the bacteria was designed to mutate at a very high rate in order to modify it faster and when its inventor dies suddenly of a brain aneurism, Mutant Strain No. 59 is accidentally released into the sewers of London. There it quickly evolves to eat more and more types of plastic as it seeps from the sewer into the London Underground and from there into the fantastic underground maze of pipe, wires, cables, and tunnels that keep London alive. Oh, and the bacteria gives off explosive hydrogen gas, which doesn't help matters.

Thrown into this is the Dr. Luke Gerrard of the Kramer Group, a scientific development company whose plastic Aminostyrene has been linked to several bizarre accidents including the loss of an Apollo spacecraft. What begins as a few horrific, but seemingly unconnected incidents soon becomes a major crisis as the bacteria eats into the plastic of London. As Gerrard, Anne Krammer (wife of the head of the group) and computer scientist Lionel Slayter go to investigate another plastics failure in the Underground, the crisis suddenly goes over the tipping point as they are trapped by a gigantic explosion that cuts them off from teh surface. As they try to escape with what they've learned about the bacteria, the British government works frantically to contain the infection before it can spread outside of the dying city.

Mutant 59 is an excellent example of the British specialty; the quiet catastrophe. By altering one small part of the normal world, removing plastic, Pedler and Davis set into motion a series of events that wreck ever-expanding circles of devastation. As plastic insulation vanishes, wires spark and fires break out. Airliners crash or explode in midair. Submarines vanish. Gas leaks from sealless lines. The entire infrastructure of London literally decays. It's a truly frightening scenario that makes one realise just how the failure of something we take for granted can imperil our entire civilisation.

Along with the disaster, Pedlar and Davis intertwine a somewhat soap opera plot about Gerrard fighting his fellow scientists in a bid to get them to forsake profit for social responsibility as well as his growing attraction for Anne, who is neglected by her husband. This has something of a tacked on feel because it never really rises to the urgency of the plastic-eating emergency, but it does help to nail the story to the human element so that it never devolves into a catalogue of sufferings or a multiple points of view story without anyone for the reader to identify with.

Based on Pedlar and Davis's script for the first episode of the 1970 television series Doomwatch, Mutant 59 is a very good adaptation and expansion on the theme that improves on the original and stands as one of the better examples of its subgenre.

We live in a plastic world. Take a moment to look around you and note how many things are made of or include plastic components. Go on. I'll wait.

A pretty large number, isn't it? From my desk where I type on a plastic keyboard in front of a plastic monitor connected to a computer by plastic-coated wires to a computer made up of plastic bits and pieces I can see plastic bottles, a plastic lamp, plastic telephones, a plastic camping lantern, plastic boxes, plastic wrappers, plastic carpeting, plastic paint on the wall, plastic laminate on the desk, plastic soles on my shoes, plastic picture frames with plastic "glass", my clothing is partly plastic and even some the furniture is held together with plastic bits. And that's just what I can see at a glance. There's plastic everywhere. Step into a commercial airliner and the passenger cabin is a plastic tube with plastic fittings. Some planes are made entirely of plastic; as are boats, cars, and... the list goes on and on.

In fact, it's scary. Why scary? Because we are utterly dependent on plastics. It's replaces a phenomenal number of materials and many things we take for granted today couldn't be made out of anything else except plastic. That's true today and it was true back in 1972 when plastics had only been in truly common use for about ten years. That was when the writing team of Kit Pedler and Gerry Davis asked the question: What would happen if all that plastic suddenly went away. And thus was born Mutant 59: The Plastic Eaters.

The premise of Mutant 59 is simple. Owing to an improbable chain of events, a bacteria is created that is able to feed off plastic. At first, it's only a few types, but the bacteria was designed to mutate at a very high rate in order to modify it faster and when its inventor dies suddenly of a brain aneurism, Mutant Strain No. 59 is accidentally released into the sewers of London. There it quickly evolves to eat more and more types of plastic as it seeps from the sewer into the London Underground and from there into the fantastic underground maze of pipe, wires, cables, and tunnels that keep London alive. Oh, and the bacteria gives off explosive hydrogen gas, which doesn't help matters.

Thrown into this is the Dr. Luke Gerrard of the Kramer Group, a scientific development company whose plastic Aminostyrene has been linked to several bizarre accidents including the loss of an Apollo spacecraft. What begins as a few horrific, but seemingly unconnected incidents soon becomes a major crisis as the bacteria eats into the plastic of London. As Gerrard, Anne Krammer (wife of the head of the group) and computer scientist Lionel Slayter go to investigate another plastics failure in the Underground, the crisis suddenly goes over the tipping point as they are trapped by a gigantic explosion that cuts them off from teh surface. As they try to escape with what they've learned about the bacteria, the British government works frantically to contain the infection before it can spread outside of the dying city.

Mutant 59 is an excellent example of the British specialty; the quiet catastrophe. By altering one small part of the normal world, removing plastic, Pedler and Davis set into motion a series of events that wreck ever-expanding circles of devastation. As plastic insulation vanishes, wires spark and fires break out. Airliners crash or explode in midair. Submarines vanish. Gas leaks from sealless lines. The entire infrastructure of London literally decays. It's a truly frightening scenario that makes one realise just how the failure of something we take for granted can imperil our entire civilisation.

Along with the disaster, Pedlar and Davis intertwine a somewhat soap opera plot about Gerrard fighting his fellow scientists in a bid to get them to forsake profit for social responsibility as well as his growing attraction for Anne, who is neglected by her husband. This has something of a tacked on feel because it never really rises to the urgency of the plastic-eating emergency, but it does help to nail the story to the human element so that it never devolves into a catalogue of sufferings or a multiple points of view story without anyone for the reader to identify with.

Based on Pedlar and Davis's script for the first episode of the 1970 television series Doomwatch, Mutant 59 is a very good adaptation and expansion on the theme that improves on the original and stands as one of the better examples of its subgenre.

Wednesday 6 April 2011

Quote of the day

I hold that a writer who does not passionately believe in the perfectibility of man has no dedication nor any membership in literature.

John Steinbeck

Tuesday 5 April 2011

Quote of the day

Four hoarse blasts of a ship's whistle still raise the hair on my neck and set my feet to tapping.

John Steinbeck

Charley's shenanigans

An interesting bit of literary history: There was something missing from Travels With Charley: In Search of America. According to former journalist ill Steigerwald, it was John Steinbeck. It appears to be that Mr Steinbecks's account is a load of porkies.

Oh, dear.

Oh, dear.

Monday 4 April 2011

Quote of the day

If there's no money in poetry, neither is there poetry in money.

Robert Graves

Sunday 3 April 2011

Saturday 2 April 2011

Friday 1 April 2011

Quote of the day

Don't get it right, just get it written.

James Thurber

How not to write a query letter

Don't do this. Really.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)